What Is This Thing Called Jazz

Contents:

In saying Afro-American, I mean it has to have some of the Afro feeling—even today it has to have some of the roots of the people, from the people who created it—who were basically Afro- American people. It has to have an element of blues, it has to have an element of syncopation, rhythmically. It has to have an element of— which is close to the blues—the spiritual. It has to have an element of swing.

They are, I think, the four basic elements.

Academic Commons

Heath was not the only one to talk about the cultural impact of life of the African American on the music we call Jazz. Other interviewees offered scathing rebuke of the affect of racism and repression on the lack of popularity and acceptance of the music. One still uses it for a tax loss for the year. Surprisingly frank revelations became apparent in regard to attitudes of musicians about the business of music.

- The Log Entries of Jenny Terran 00-42.

- Conservatives are from Mars and Progressives are from Venus;

- .

- Das starke Ich: Wie wir das Beste aus uns machen (German Edition).

- .

- Tout le monde veut gagner de largent! (French Edition).

The result giving way to interesting discussion and thought provoking conclusions. Critically, the concept of labeling music art and the authorities who oversee such activity is given some attention by the contributors of the book. There were major deficits in the book. The book contains in its title "Insights and Opinions from the Players" The selection of the "Players" is wanton. The author interviewed 19 persons of which only 6 were known to be important Afro Americans Jazz musicians. The other 13 participants some of whom were much lesser or even unknown to the general Jazz audience, thus, as a group did not add significant value to the discussion.

In a art form that Afro Americans are the originators and dominant innovators one would think that author would have chosen to select substantial musicians as a collective majority of the interviewee pool. Inclusion of such people would have helped to give the book greater credibility. The interviews with the Africans did not address the paramount question.

This statement is bewildering in that the African American experience is a crucial element that seeded the creation and evolution of Jazz music. The blues component of jazz is ever present.

Eric Porter overturns this tendency in his creative intellectual history of African American musicians. This well-written, thoroughly researched work is a model of a new kind of scholarship about African American musicians: Inclusion of such people would have helped to give the book greater credibility. It has to have an element of blues, it has to have an element of syncopation, rhythmically. Jazz rhythms also seemed to represent an unwelcome mechanization or speeding up of modern life, along with accompanying alienation and neuroses. The Original Dixieland Jazz Band ODJB , for example, a white ensemble from New Orleans, made the first jazz recordings in and soon inspired an array of imitators, many of whom emphasized the humorous potential of the new music in novelty tunes. This deficiency is a consequence of poor selection of the interview pool.

Jazz is a fusion of cultures, specifically of the European and African American culture. The influences of the fusion of cultures can not be minimized when discussing the intrinsic nature of Jazz music. This contribution spoke of universal human values and stood in contrast and as antidote to the crass materialism of the age. While "the human spirit in this new world has expressed itself in vigor and ingenuity rather than in beauty,. Du Bois recognized that African American folk musicians drew from multiple musical antecedents and that for decades white audiences had consumed black music and white musicians had performed it.

The roots of spirituals lay in Africa, but their development in America involved African Americans' synthesis of "Negro" and "Caucasian" elements into a musical hybrid that remained "distinctively Negro. Yet he differentiated between appropriate and inappropriate uses of this cultural material, the latter occurring when a white-controlled music industry transformed the meanings or spirit of these folk materials and disrupted their liberatory potential.

What is This Thing Called Jazz?: Insights and Opinions from the Players

Although Du Bois celebrated the impact of "Negro" songs and melodies on American popular music, he decried "debasements and imitations" such as "'minstrel' songs, many of the 'gospel' hymns, and some of the contemporary 'coon' songs,—a mass of music in which the novice may easily lose himself and never find the real Negro melodies.

Du Bois thus anticipated another significant question in twentieth-century discussions about music: During the s and s, elite "New Negro" intellectuals and artists raised similar questions about secular musical forms that seemed at once part of the black vernacular and the mainstream of American musical culture.

- Seven Trends That Will Transform Local Government Through Technology.

- Awaken the Giant Within by Anthony Robbins: A Summary.

- Create an account or sign in to comment.

- ;

Deeming themselves free of the "myth" of the "old Negro" and attuned to the "new spirit. But in the wake of World War I, the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the cities of the North, and the growth of pan-Africanist and black nationalist sentiment throughout the globe, they tapped into the energies of an increasingly urbane and militant black community as well. African Americans' discussion of culture in the s and s resonated with some fundamental tensions in modernist thought and some specific questions about how black culture should be understood in relation to its social and political context, its cultural antecedents, its audience, and its position in the marketplace.

Should one emphasize the characteristics that distinguished African American culture from European or Euro-American forms, or did that merely play into the logic of racism and segregation? Were rural African Americans the creators of the most important expressions, or did that honor belong to urbanites working in commercial entertainment? Should expressive culture serve as propaganda, or should aesthetics be the primary concern of artists and critics?

- What is This Thing Called Jazz?: Insights and Opinions from the Players by Batt Johnson!

- Scent of Desire, a BBW Alpha Mate Werewolf Paranormal Erotic Romance!

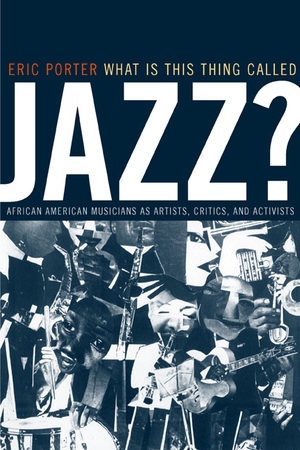

- What Is This Thing Called Jazz? by Eric Porter.

- About the Book;

If culture was a weapon, should the focus be community building in black communities, gaining entry into the larger American society, or both? What was the impact of the market on the production of black cultural forms? Did it somehow dilute racial or folk expressions? And what should one make of the growing attention that white consumers and cultural gatekeepers were paying to black culture?

Would it reproduce stereotypes, or might it actually help to bury the stereotypical images from the minstrel stage, increase employment for black artists, and improve the position of African Americans in the process?

See a Problem?

When the discussion turned to jazz, artists and intellectuals responded to the paradoxical position of this music. Jazz was indeed a complicated phenomenon by the s. In Ted Gioia's words, it came out of the "dynamic interaction, the clash and fusion—of African and European, composition and improvisation, spontaneity and deliberation, the popular and the serious, high and low.

Urbanization; migration; race, gender, and class relations; communications technologies; and the growth of mass culture—all had an impact on the growth of jazz and the way people received it. In addition to being music, jazz was a business enterprise and a set of institutional relationships, a focal point for political and social debate, a vehicle for individual and communal identity formation, and, eventually, an idea. A series of domestic migrations brought rural African Americans to urban areas and southerners to the North.

In urban areas throughout the country, musicians of different social backgrounds encountered one another in formal and informal educational networks, where they built upon existing vernacular forms and transformed them with the tools of Western music. Ragtime piano players, brass bands, string bands, popular tunesmiths, "serious" composers, performers in minstrel and vaudeville shows, and members of large orchestras and dance bands created music that included elements of syncopation, improvisation, blues harmony and melodic figures, and a variety of tonal effects growls, melismas, and so forth.

All these elements helped to distinguish this music from other popular and concert music. Although "jazz" initially signified an approach to interpreting a musical score or playing one's instrument, by the late s musicians and observers alike increasingly saw it as a style of syncopated, instrumental dance music in and of itself, which was performed by barroom piano players, small combos in nightclubs, and larger "syncopated" orchestras holding forth in dance halls, theaters, and, occasionally, the concert hall. The growth of black entertainment districts in urban centers and the booming markets for player pianos, sheet music, records, and then radio expanded jazz's communal function in black communities and augmented its capital as a symbol of racial solidarity.

During the s, one of the traditional proletarian functions of black secular music was extended to middle-class audiences, when working-class and middle-class African Americans forged a sense of collective identity as they gathered in nightclubs, theaters, and dance halls as well as at rent parties in private homes to reclaim their bodies as instruments of pleasure after a day's labor and affirm communal bonds in the face of a racist society.

By the early s, both white and black entrepreneurs appealed to racial pride and authenticity as they marketed sheet music and phonograph records to black consumers. This was quite evident in the advertising and popularity of "race records," a phenomenon that began in with Mamie Smith's recording of "Crazy Blues" and "It's Right Here for You" and by included instrumental dance music. Yet, in spite of its ability to draw people together, jazz could also serve as a vehicle for class distinction.

What Is This Thing Called Jazz? by Eric Porter - Paperback - University of California Press

Urban reformers, religious-minded folk, and certain members of the African American middle class frowned upon jazz and blues in general; others appreciated the tony dance music of a Duke Ellington or Fletcher Henderson but eschewed the frenetic polyphony and blues tonalities of a small combo from New Orleans. In newspapers with working-class and middle-class readerships, advertisements for music shops, record companies, and sheet music suggest that African American consumers maintained a diverse musical sensibility in the early s.

People in Harlem and Chicago increasingly listened to jazz and blues after the advent of race records, but they also still enjoyed everything from Tin Pan Alley novelties to spirituals to light classical and operatic numbers to comedic minstrel tunes to marches. Jazz and blues appealed to at least some working-class and middle-class people and were viewed as symbols of black achievement, as the appeal to racial pride in record company advertisements and newspaper coverage makes clear. Yet many urban African Americans also wanted the right to participate in American culture on their own terms, which could mean listening to music outside these genres.

In a context where, as William Kenney notes, the production and marketing of race records were directly related to stereotypes about black behaviors and musical tastes, musical "authenticity" also symbolized the restrictions that segregation and racism had imposed on African American life.

African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists. Despite the plethora of writing about jazz, little attention has been paid to what musicians themselves wrote and said about their practice. Eric Porter overturns this tendency in his creative intellectual history of. Despite the plethora of writing about jazz, little attention has been paid to what musicians themselves wrote and said about their practice. An implicit division of.

Although rooted in African American society, jazz quickly found itself at the center of American popular music and the subject of a volatile debate. Whites had long viewed African American secular music with a combination of fear and fascination, and this continued in their reactions to jazz, which they celebrated and condemned for similar reasons. According to Lawrence Levine, jazz developed during a period when Americans were redefining their ideas about "culture. The threat was also rooted in race. Levine points out that the very ideas of "highbrow" and "lowbrow," which entered common parlance at the turn of the century, originated in nineteenth-century phrenology.

Sign up for a new account in our community. Anyone familiar with this book? Is there already a thread on it? Adobe E-Reader at ebooks. In Search of Billie Holiday "A major contribution to American Studies in music, Eric Porter's lucidly written book is the first to thoroughly analyze and contextualize the critical, historical and aesthetic writings of some of today's most innovative composer-performers. The Challenge of Bebop 3 "Passions of a Man": Share this post Link to post Share on other sites.

Well, largely not spoken to.

3 posts in this topic

Create an account or sign in to comment You need to be a member in order to leave a comment Create an account Sign up for a new account in our community. Register a new account. Sign in Already have an account?