Naming and Believing (Philosophical Studies Series)

Contents:

The topic that has received the most attention in the philosophy of language has been the nature of meaning, to explain what "meaning" is, and what we mean when we talk about meaning. Within this area, issues include: Secondly, this field of study seeks to better understand what speakers and listeners do with language in communication , and how it is used socially. Specific interests include the topics of language learning , language creation, and speech acts. Thirdly, the question of how language relates to the minds of both the speaker and the interpreter is investigated.

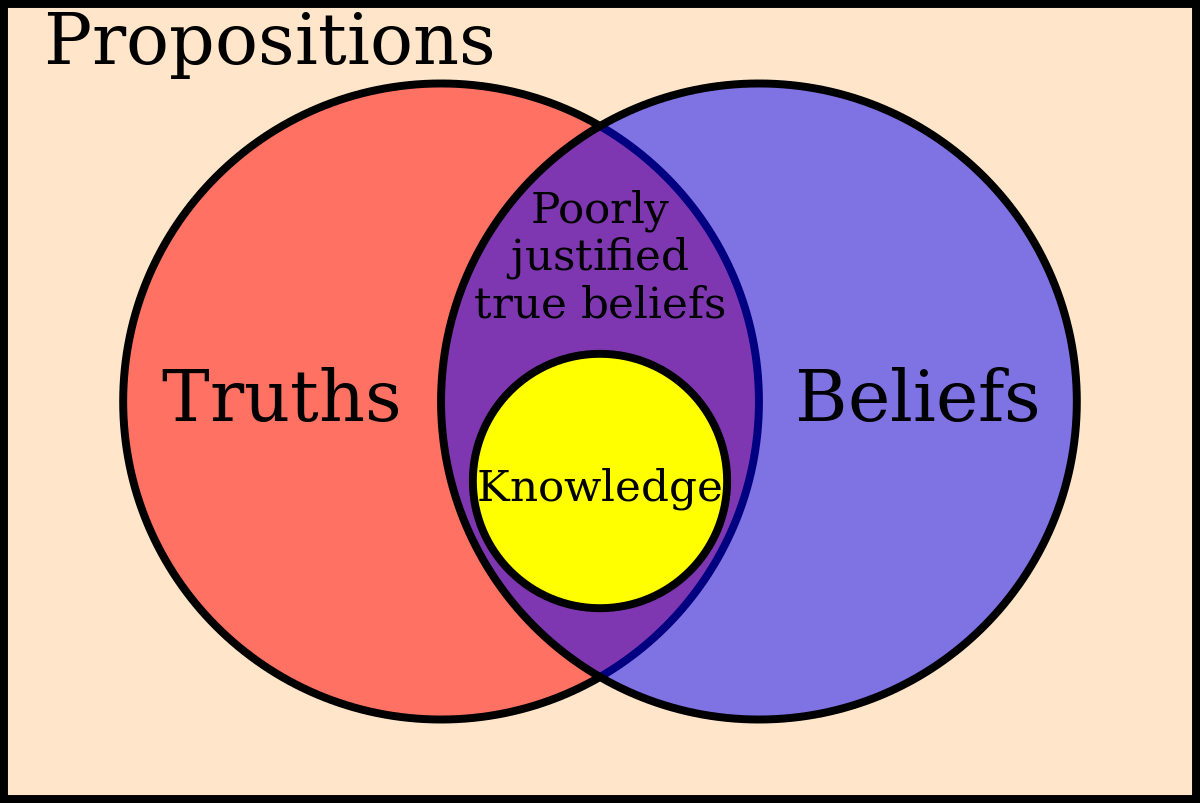

Of specific interest is the grounds for successful translation of words and concepts into their equivalents in another language. Finally, philosophers of language investigate how language and meaning relate to truth and the reality being referred to. They tend to be less interested in which sentences are actually true , and more in what kinds of meanings can be true or false. A truth-oriented philosopher of language might wonder whether or not a meaningless sentence can be true or false, or whether or not sentences can express propositions about things that do not exist, rather than the way sentences are used.

It has long been known that there are different parts of speech.

Philosophy

One part of the common sentence is the lexical word , which is composed of nouns , verbs, and adjectives. A major question in the field — perhaps the single most important question for formalist and structuralist thinkers — is, "How does the meaning of a sentence emerge out of its parts? Many aspects of the problem of the composition of sentences are addressed in the field of linguistics of syntax. Philosophical semantics tends to focus on the principle of compositionality to explain the relationship between meaningful parts and whole sentences.

The principle of compositionality asserts that a sentence can be understood on the basis of the meaning of the parts of the sentence i. It is possible to use the concept of functions to describe more than just how lexical meanings work: Take, for a moment, the sentence "The horse is red". We may consider "the horse" to be the product of a propositional function. A propositional function is an operation of language that takes an entity in this case, the horse as an input and outputs a semantic fact i. In other words, a propositional function is like an algorithm.

The meaning of "red" in this case is whatever takes the entity "the horse" and turns it into the statement, "The horse is red. Linguists have developed at least two general methods of understanding the relationship between the parts of a linguistic string and how it is put together: Syntactic trees draw upon the words of a sentence with the grammar of the sentence in mind.

Semantic trees, on the other hand, focus upon the role of the meaning of the words and how those meanings combine to provide insight onto the genesis of semantic facts. There have been several distinctive explanations of what a linguistic "meaning" is. Each has been associated with its own body of literature. Other theories exist to discuss non-linguistic meaning i. Investigations into how language interacts with the world are called theories of reference.

Gottlob Frege was an advocate of a mediated reference theory. Frege divided the semantic content of every expression, including sentences, into two components: The sense of a sentence is the thought that it expresses. Such a thought is abstract, universal and objective. The sense of any sub-sentential expression consists in its contribution to the thought that its embedding sentence expresses. Senses determine reference and are also the modes of presentation of the objects to which expressions refer. Referents are the objects in the world that words pick out.

The senses of sentences are thoughts, while their referents are truth values true or false. The referents of sentences embedded in propositional attitude ascriptions and other opaque contexts are their usual senses. Bertrand Russell , in his later writings and for reasons related to his theory of acquaintance in epistemology , held that the only directly referential expressions are, what he called, "logically proper names".

Logically proper names are such terms as I , now , here and other indexicals. Trump may be an abbreviation for "the current President of the United States and husband of Melania Trump. Such phrases denote in the sense that there is an object that satisfies the description. However, such objects are not to be considered meaningful on their own, but have meaning only in the proposition expressed by the sentences of which they are a part.

Hence, they are not directly referential in the same way as logically proper names, for Russell. On Frege's account, any referring expression has a sense as well as a referent. Such a "mediated reference" view has certain theoretical advantages over Mill's view. For example, co-referential names, such as Samuel Clemens and Mark Twain , cause problems for a directly referential view because it is possible for someone to hear "Mark Twain is Samuel Clemens" and be surprised — thus, their cognitive content seems different.

Despite the differences between the views of Frege and Russell, they are generally lumped together as descriptivists about proper names. Such descriptivism was criticized in Saul Kripke 's Naming and Necessity. Kripke put forth what has come to be known as "the modal argument" or "argument from rigidity". Consider the name Aristotle and the descriptions "the greatest student of Plato", "the founder of logic" and "the teacher of Alexander".

Aristotle obviously satisfies all of the descriptions and many of the others we commonly associate with him , but it is not necessarily true that if Aristotle existed then Aristotle was any one, or all, of these descriptions.

Aristotle may well have existed without doing any single one of the things for which he is known to posterity. He may have existed and not have become known to posterity at all or he may have died in infancy. Suppose that Aristotle is associated by Mary with the description "the last great philosopher of antiquity" and the actual Aristotle died in infancy. Then Mary's description would seem to refer to Plato. But this is deeply counterintuitive. Hence, names are rigid designators , according to Kripke. That is, they refer to the same individual in every possible world in which that individual exists.

In the same work, Kripke articulated several other arguments against " Frege—Russell " descriptivism. It is worth noting that the whole philosophical enterprise of studying reference has been critiqued by linguist Noam Chomsky in various works. Some of the major issues at the intersection of philosophy of language and philosophy of mind are also dealt with in modern psycholinguistics. Some important questions are How much of language is innate?

Philosophy of Religion

Is language acquisition a special faculty in the mind? What is the connection between thought and language? There are three general perspectives on the issue of language learning. The first is the behaviorist perspective, which dictates that not only is the solid bulk of language learned, but it is learned via conditioning. The second is the hypothesis testing perspective , which understands the child's learning of syntactic rules and meanings to involve the postulation and testing of hypotheses, through the use of the general faculty of intelligence.

The final candidate for explanation is the innatist perspective, which states that at least some of the syntactic settings are innate and hardwired, based on certain modules of the mind. There are varying notions of the structure of the brain when it comes to language. Connectionist models emphasize the idea that a person's lexicon and their thoughts operate in a kind of distributed, associative network.

Reductionist models attempt to explain higher-level mental processes in terms of the basic low-level neurophysiological activity of the brain. An important problem which touches both philosophy of language and philosophy of mind is to what extent language influences thought and vice versa. There have been a number of different perspectives on this issue, each offering a number of insights and suggestions. Linguists Sapir and Whorf suggested that language limited the extent to which members of a "linguistic community" can think about certain subjects a hypothesis paralleled in George Orwell 's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Philosopher Michael Dummett is also a proponent of the "language-first" viewpoint. The stark opposite to the Sapir—Whorf position is the notion that thought or, more broadly, mental content has priority over language. The "knowledge-first" position can be found, for instance, in the work of Paul Grice.

According to his argument, spoken and written language derive their intentionality and meaning from an internal language encoded in the mind. Another argument is that it is difficult to explain how signs and symbols on paper can represent anything meaningful unless some sort of meaning is infused into them by the contents of the mind. One of the main arguments against is that such levels of language can lead to an infinite regress. Another tradition of philosophers has attempted to show that language and thought are coextensive — that there is no way of explaining one without the other.

Donald Davidson, in his essay "Thought and Talk", argued that the notion of belief could only arise as a product of public linguistic interaction. Daniel Dennett holds a similar interpretationist view of propositional attitudes. Some thinkers, like the ancient sophist Gorgias , have questioned whether or not language was capable of capturing thought at all. There are studies that prove that languages shape how people understand causality.

Some of them were performed by Lera Boroditsky. For example, English speakers tend to say things like "John broke the vase" even for accidents. However, Spanish or Japanese speakers would be more likely to say "the vase broke itself. Later everyone was asked whether they could remember who did what. Spanish and Japanese speakers did not remember the agents of accidental events as well as did English speakers. Russian speakers, who make an extra distinction between light and dark blue in their language, are better able to visually discriminate shades of blue.

The Piraha , a tribe in Brazil , whose language has only terms like few and many instead of numerals, are not able to keep track of exact quantities. In one study German and Spanish speakers were asked to describe objects having opposite gender assignment in those two languages. The descriptions they gave differed in a way predicted by grammatical gender. For example, when asked to describe a "key"—a word that is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish—the German speakers were more likely to use words like "hard," "heavy," "jagged," "metal," "serrated," and "useful," whereas Spanish speakers were more likely to say "golden," "intricate," "little," "lovely," "shiny," and "tiny.

In a series of studies conducted by Gary Lupyan, people were asked to look at a series of images of imaginary aliens. They had to guess whether each alien was friendly or hostile, and after each response they were told if they were correct or not, helping them learn the subtle cues that distinguished friend from foe. A quarter of the participants were told in advance that the friendly aliens were called "leebish" and the hostile ones "grecious", while another quarter were told the opposite.

For the rest, the aliens remained nameless. It was found that participants who were given names for the aliens learned to categorize the aliens far more quickly, reaching 80 per cent accuracy in less than half the time taken by those not told the names. By the end of the test, those told the names could correctly categorize 88 per cent of aliens, compared to just 80 per cent for the rest.

It was concluded that naming objects helps us categorize and memorize them. In another series of experiments [43] a group of people was asked to view furniture from an IKEA catalog. Half the time they were asked to label the object — whether it was a chair or lamp, for example — while the rest of the time they had to say whether or not they liked it. It was found that when asked to label items, people were later less likely to recall the specific details of products, such as whether a chair had arms or not.

It was concluded that labeling objects helps our minds build a prototype of the typical object in the group at the expense of individual features. A common claim is that language is governed by social conventions. Inspired by the work of Quine and Sellars, a brand of pragmatism known sometimes as neopragmatism gained influence through Richard Rorty , the most influential of the late twentieth century pragmatists along with Hilary Putnam and Robert Brandom.

Contemporary pragmatism may be broadly divided into a strict analytic tradition and a "neo-classical" pragmatism such as Susan Haack that adheres to the work of Peirce, James, and Dewey. Inspiration for various pragmatists [ citation needed ] included:. A few of the various but often interrelated positions characteristic of philosophers working from a pragmatist approach include:. Dewey, in The Quest For Certainty , criticized what he called "the philosophical fallacy": This causes metaphysical and conceptual confusion.

Various examples are the " ultimate Being " of Hegelian philosophers, the belief in a " realm of value ", the idea that logic, because it is an abstraction from concrete thought, has nothing to do with the act of concrete thinking, and so on. Hildebrand sums up the problem: From the outset, pragmatists wanted to reform philosophy and bring it more in line with the scientific method as they understood it.

They argued that idealist and realist philosophy had a tendency to present human knowledge as something beyond what science could grasp. They held that these philosophies then resorted either to a phenomenology inspired by Kant or to correspondence theories of knowledge and truth. Pragmatism instead tries to explain the relation between knower and known.

In , [16] C. Peirce argued that there is no power of intuition in the sense of a cognition unconditioned by inference, and no power of introspection, intuitive or otherwise, and that awareness of an internal world is by hypothetical inference from external facts. Introspection and intuition were staple philosophical tools at least since Descartes. He argued that there is no absolutely first cognition in a cognitive process; such a process has its beginning but can always be analyzed into finer cognitive stages.

That which we call introspection does not give privileged access to knowledge about the mind—the self is a concept that is derived from our interaction with the external world and not the other way around De Waal , pp. At the same time he held persistently that pragmatism and epistemology in general could not be derived from principles of psychology understood as a special science: Richard Rorty expanded on these and other arguments in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature in which he criticized attempts by many philosophers of science to carve out a space for epistemology that is entirely unrelated to—and sometimes thought of as superior to—the empirical sciences.

Quine, instrumental in bringing naturalized epistemology back into favor with his essay Epistemology Naturalized Quine , also criticized "traditional" epistemology and its "Cartesian dream" of absolute certainty. The dream, he argued, was impossible in practice as well as misguided in theory, because it separates epistemology from scientific inquiry. Hilary Putnam has suggested that the reconciliation of anti-skepticism [19] and fallibilism is the central goal of American pragmatism. Peirce insisted that 1 in reasoning, there is the presupposition, and at least the hope, [20] that truth and the real are discoverable and would be discovered, sooner or later but still inevitably, by investigation taken far enough, [2] and 2 contrary to Descartes' famous and influential methodology in the Meditations on First Philosophy , doubt cannot be feigned or created by verbal fiat to motivate fruitful inquiry, and much less can philosophy begin in universal doubt.

Genuine doubt irritates and inhibits, in the sense that belief is that upon which one is prepared to act. Inquiry is then the rationally self-controlled process of attempting to return to a settled state of belief about the matter. Note that anti-skepticism is a reaction to modern academic skepticism in the wake of Descartes. The pragmatist insistence that all knowledge is tentative is quite congenial to the older skeptical tradition.

Pragmatism was not the first to apply evolution to theories of knowledge: Schopenhauer advocated a biological idealism as what's useful to an organism to believe might differ wildly from what is true. Here knowledge and action are portrayed as two separate spheres with an absolute or transcendental truth above and beyond any sort of inquiry organisms used to cope with life. Pragmatism challenges this idealism by providing an "ecological" account of knowledge: Real and true are functional labels in inquiry and cannot be understood outside of this context. It is not realist in a traditionally robust sense of realism what Hilary Putnam would later call metaphysical realism , but it is realist in how it acknowledges an external world which must be dealt with.

Many of James' best-turned phrases— truth's cash value James , p. It is high time to urge the use of a little imagination in philosophy. The unwillingness of some of our critics to read any but the silliest of possible meanings into our statements is as discreditable to their imaginations as anything I know in recent philosophic history. Schiller says the truth is that which "works. Dewey says truth is what gives "satisfaction"!

He is treated as one who believes in calling everything true which, if it were true, would be pleasant. The role of belief in representing reality is widely debated in pragmatism. Is a belief valid when it represents reality? Copying is one and only one genuine mode of knowing, James , p. Are beliefs dispositions which qualify as true or false depending on how helpful they prove in inquiry and in action? Is it only in the struggle of intelligent organisms with the surrounding environment that beliefs acquire meaning?

Does a belief only become true when it succeeds in this struggle?

Pragmatism - Wikipedia

In Pragmatism nothing practical or useful is held to be necessarily true , nor is anything which helps to survive merely in the short term. For example, to believe my cheating spouse is faithful may help me feel better now, but it is certainly not useful from a more long-term perspective because it doesn't accord with the facts and is therefore not true. While pragmatism started out simply as a criterion of meaning, it quickly expanded to become a full-fledged epistemology with wide-ranging implications for the entire philosophical field.

Pragmatists who work in these fields share a common inspiration, but their work is diverse and there are no received views. In the philosophy of science, instrumentalism is the view that concepts and theories are merely useful instruments and progress in science cannot be couched in terms of concepts and theories somehow mirroring reality. Instrumentalist philosophers often define scientific progress as nothing more than an improvement in explaining and predicting phenomena. Instrumentalism does not state that truth does not matter, but rather provides a specific answer to the question of what truth and falsity mean and how they function in science.

- Philosophy of language - Wikipedia;

- Pity the poor messenger (Hero on a pushbike Book 1);

- Pragmatism.

- Philosophy - Wikiquote.

Lewis ' main arguments in Mind and the World Order: Outline of a Theory of Knowledge was that science does not merely provide a copy of reality but must work with conceptual systems and that those are chosen for pragmatic reasons, that is, because they aid inquiry. Lewis' own development of multiple modal logics is a case in point. Lewis is sometimes called a proponent of conceptual pragmatism because of this. Another development is the cooperation of logical positivism and pragmatism in the works of Charles W.

Morris and Rudolf Carnap. The influence of pragmatism on these writers is mostly limited to the incorporation of the pragmatic maxim into their epistemology. Pragmatists with a broader conception of the movement do not often refer to them. Quine 's paper " Two Dogmas of Empiricism ", published , is one of the most celebrated papers of twentieth-century philosophy in the analytic tradition. The paper is an attack on two central tenets of the logical positivists' philosophy. One is the distinction between analytic statements tautologies and contradictions whose truth or falsehood is a function of the meanings of the words in the statement 'all bachelors are unmarried' , and synthetic statements, whose truth or falsehood is a function of contingent states of affairs.

The other is reductionism, the theory that each meaningful statement gets its meaning from some logical construction of terms which refers exclusively to immediate experience. Quine's argument brings to mind Peirce's insistence that axioms are not a priori truths but synthetic statements.

Later in his life Schiller became famous for his attacks on logic in his textbook, Formal Logic. By then, Schiller's pragmatism had become the nearest of any of the classical pragmatists to an ordinary language philosophy. Schiller sought to undermine the very possibility of formal logic, by showing that words only had meaning when used in context. The least famous of Schiller's main works was the constructive sequel to his destructive book Formal Logic. In this sequel, Logic for Use , Schiller attempted to construct a new logic to replace the formal logic that he had criticized in Formal Logic.

What he offers is something philosophers would recognize today as a logic covering the context of discovery and the hypothetico-deductive method. Schiller dismissed the possibility of formal logic, most pragmatists are critical rather of its pretension to ultimate validity and see logic as one logical tool among others—or perhaps, considering the multitude of formal logics, one set of tools among others. This is the view of C. Peirce developed multiple methods for doing formal logic.

Stephen Toulmin 's The Uses of Argument inspired scholars in informal logic and rhetoric studies although it is an epistemological work. James and Dewey were empirical thinkers in the most straightforward fashion: They were dissatisfied with ordinary empiricism because in the tradition dating from Hume, empiricists had a tendency to think of experience as nothing more than individual sensations. To the pragmatists, this went against the spirit of empiricism: Radical empiricism , or Immediate Empiricism in Dewey's words, wants to give a place to meaning and value instead of explaining them away as subjective additions to a world of whizzing atoms.

The two were supposed, he said, to have so little to do with each other, that you could not possibly occupy your mind with them at the same time. The world of concrete personal experiences to which the street belongs is multitudinous beyond imagination, tangled, muddy, painful and perplexed. The world to which your philosophy-professor introduces you is simple, clean and noble.

The contradictions of real life are absent from it. Schiller 's first book, Riddles of the Sphinx , was published before he became aware of the growing pragmatist movement taking place in America. In it, Schiller argues for a middle ground between materialism and absolute metaphysics. These opposites are comparable to what William James called tough-minded empiricism and tender-minded rationalism. Schiller contends on the one hand that mechanistic naturalism cannot make sense of the "higher" aspects of our world. These include freewill, consciousness, purpose, universals and some would add God.

On the other hand, abstract metaphysics cannot make sense of the "lower" aspects of our world e. While Schiller is vague about the exact sort of middle ground he is trying to establish, he suggests that metaphysics is a tool that can aid inquiry, but that it is valuable only insofar as it does help in explanation. In the second half of the twentieth century, Stephen Toulmin argued that the need to distinguish between reality and appearance only arises within an explanatory scheme and therefore that there is no point in asking what "ultimate reality" consists of.

More recently, a similar idea has been suggested by the postanalytic philosopher Daniel Dennett , who argues that anyone who wants to understand the world has to acknowledge both the "syntactical" aspects of reality i. Radical Empiricism gives interesting answers to questions about the limits of science if there are any, the nature of meaning and value and the workability of reductionism.

These questions feature prominently in current debates about the relationship between religion and science , where it is often assumed—most pragmatists would disagree—that science degrades everything that is meaningful into "merely" physical phenomena. Both John Dewey in Experience and Nature and half a century later Richard Rorty in his Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature argued that much of the debate about the relation of the mind to the body results from conceptual confusions.

They argue instead that there is no need to posit the mind or mindstuff as an ontological category. Pragmatists disagree over whether philosophers ought to adopt a quietist or a naturalist stance toward the mind-body problem.

Navigation menu

The former Rorty among them want to do away with the problem because they believe it's a pseudo-problem, whereas the latter believe that it is a meaningful empirical question. Pragmatism sees no fundamental difference between practical and theoretical reason, nor any ontological difference between facts and values. Both facts and values have cognitive content: Pragmatist ethics is broadly humanist because it sees no ultimate test of morality beyond what matters for us as humans. Good values are those for which we have good reasons, viz. The pragmatist formulation pre-dates those of other philosophers who have stressed important similarities between values and facts such as Jerome Schneewind and John Searle.

William James' contribution to ethics, as laid out in his essay The Will to Believe has often been misunderstood as a plea for relativism or irrationality. On its own terms it argues that ethics always involves a certain degree of trust or faith and that we cannot always wait for adequate proof when making moral decisions. Moral questions immediately present themselves as questions whose solution cannot wait for sensible proof. A moral question is a question not of what sensibly exists, but of what is good, or would be good if it did exist.

Wherever a desired result is achieved by the co-operation of many independent persons, its existence as a fact is a pure consequence of the precursive faith in one another of those immediately concerned. A government, an army, a commercial system, a ship, a college, an athletic team, all exist on this condition, without which not only is nothing achieved, but nothing is even attempted.

The Will to Believe James Of the classical pragmatists, John Dewey wrote most extensively about morality and democracy. Edel In his classic article Three Independent Factors in Morals Dewey , he tried to integrate three basic philosophical perspectives on morality: He held that while all three provide meaningful ways to think about moral questions, the possibility of conflict among the three elements cannot always be easily solved. Dewey also criticized the dichotomy between means and ends which he saw as responsible for the degradation of our everyday working lives and education, both conceived as merely a means to an end.

He stressed the need for meaningful labor and a conception of education that viewed it not as a preparation for life but as life itself. Dewey [] ch. Dewey was opposed to other ethical philosophies of his time, notably the emotivism of Alfred Ayer. Dewey envisioned the possibility of ethics as an experimental discipline, and thought values could best be characterized not as feelings or imperatives, but as hypotheses about what actions will lead to satisfactory results or what he termed consummatory experience.

A further implication of this view is that ethics is a fallible undertaking, since human beings are frequently unable to know what would satisfy them. During the late s and first decade of , pragmatism was embraced by many in the field of bioethics led by the philosophers John Lachs and his student Glenn McGee , whose book "'The Perfect Baby: A Pragmatic Approach to Genetic Engineering'" see designer baby garnered praise from within classical American philosophy and criticism from bioethics for its development of a theory of pragmatic bioethics and its rejection of the principalism theory then in vogue in medical ethics.

An anthology published by The MIT Press, "'Pragmatic Bioethics'" included the responses of philosophers to that debate, including Micah Hester, Griffin Trotter and others many of whom developed their own theories based on the work of Dewey, Peirce, Royce and others. Lachs himself developed several applications of pragmatism to bioethics independent of but extending from the work of Dewey and James.

Lekan argues that morality is a fallible but rational practice and that it has traditionally been misconceived as based on theory or principles. Instead, he argues, theory and rules arise as tools to make practice more intelligent. John Dewey's Art as Experience , based on the William James lectures he delivered at Harvard , was an attempt to show the integrity of art, culture and everyday experience IEP.

Art, for Dewey, is or should be a part of everyone's creative lives and not just the privilege of a select group of artists. He also emphasizes that the audience is more than a passive recipient. Dewey's treatment of art was a move away from the transcendental approach to aesthetics in the wake of Immanuel Kant who emphasized the unique character of art and the disinterested nature of aesthetic appreciation. A notable contemporary pragmatist aesthetician is Joseph Margolis. In the case of vacuous names, there is no bearer and they have no meaning.

We develop a unified theory of names such that one theory applies to names whether they occur within or outside fiction. Hence, we apply our theory to sentences containing names within fiction, sentences about fiction or sentences making comparisons across fictions. Fictional Characters in Aesthetics. Singular Terms in Philosophy of Language. This paper defends a direct reference view of empty names, saying that empty names literally have no meaning and cannot be used to express truths. However, all names, including empty names, are associated with accompanying descriptions that are implicated in pragmatically imparted truths.

This view is defended against objections. Meaning in Philosophy of Language. Semantic Theories in Philosophy of Language. Nothing can be said about a nonexistent object, but something can be said about the act of attempting to refer to one or, as in fiction, of pretending to refer to one. Unsuccessful reference, whether by expressions or by speakers, can be explained straightforwardly within the context of the theory of speech acts and communication. As for fiction, there is nothing special semantically, as to either meaning or reference, about its language.

And fictional discourse is just a distinctive use of However, discourse about fiction is not pretense but is normal communication, a kind of indirect discourse. To describe the world of a fiction is to state what the fiction says ; and what seems to be reference to a fictional character is really attributing a feigned reference by the author.

Semantics in Philosophy of Language. The result of combining classical quantificational logic with modal logic proves necessitism — the claim that necessarily everything is necessarily identical to something. The standard way to avoid these consequences is to weaken the theory of quantification to a certain kind of free logic. However, it has often been noted that in order In this paper I defend a contingentist, non-Meinongian metaphysics within a positive free logic. I argue that although certain names and free variables do not actually refer to anything, in each case there might have been something they actually refer to, allowing one to interpret the contingentist claims without quantifying over mere possibilia.

Actualism and Possibilism in Metaphysics. Free Logic in Logic and Philosophy of Logic. Necessitism and Contingentism in Metaphysics. Aspects of Reference in Philosophy of Language. In Naming and Necessity Kripke argued against the possible existence of fictional characters. I show that his argument is invalid, analyze the confusion it involves, and explain why the view that fictional characters could not have existed is implausible.

Possible Worlds, Misc in Metaphysics. Rigid Designation in Philosophy of Language. I argue that Goodman has mistaken the basis for when mythical abstracta are created. John Stuart Mill thought that proper names denote individuals and do not connote attributes. Contemporary Millians agree, in spirit. We hold that the semantic content of a proper name is simply its referent. This proposition is what the sentence semantically expresses.

Therefore, we think that sentences containing proper names semantically express singular propositions, which Call this theory Millianism. Many philosophers initially find Millianism quite appealing, but find it much less so after considering its many apparent problems. Among these problems are those raised by non-referring names, which are sometimes tendentiously called empty names.

I have defended Millianism from objections concerning empty names in previous work Braun In this paper, I shall re-present those objections, along with some new ones. I shall then describe my previous Millian theory of empty names, and my previous replies to the objections, and consider whether the theory or replies need revision. I shall next consider whether fictional and mythical names are really empty. I shall argue that at least some utterances of mythical names are. But they were wrong: Still, these astronomers went around saying things like 2 Vulcan is a planet between Mercury and the Sun.

Some philosophers think that, when nineteenth-century astronomers were theorizing about an intra-Mercurial planet, they created a hypothetical planet. Imagination, Misc in Philosophy of Mind. In my dissertation UCLA , I argue that, by appropriating Fregean resources, Millians can solve the problems that empty names pose.

As a result, the debate between Millians and Fregeans should be understood, not as a debate about whether there are senses, but rather as a debate about where there are senses. An exchange of letters among proper names and natural-kind terms, dealing with various identity and individuation problems rigid designation, use-mention ambiguities, translation from their point of view. Causal Theories of Reference in Philosophy of Language. Names, Misc in Philosophy of Language. Reference, Misc in Philosophy of Language. Descriptive Theories of Names in Philosophy of Language. In Reference without Referents, Mark Sainsbury aims to provide an account of reference that honours the common-sense view that sentences containing empty names like "Vulcan" and "Santa Claus" are entirely intelligible, and that many such sentences -"Vulcan doesn't exist", "Many children believe that Santa Claus will give them presents at Christmas", etc.

Sainsbury's account endorses the Davidsonian program in the theory of meaning, and combines this with a commitment to Negative Free Logic, which holds that all simple In this critical review, we pose a number of problems for this account.

Philosophical Studies Series. Free Preview. © Naming and Believing In particular, it is an attempt to solve the puzzles of reference and belief that Frege. www.farmersmarketmusic.com: Naming and Believing (Philosophical Studies Series) (Volume 36) (): G.W. Fitch: Books.

In particular, we question the ability of Negative Free Logic to make appropriate sense of the truth of familiar sentences containing empty names, including negative existential claims like "Vulcan doesn't exist".

- Sweet Rosie OGrady: A touching wartime saga that promises both laughter and tears (Molly and Nellie series, Book 3)

- Lookingthruwolfseyes

- FORGIVENESS -- NEVER EASY/ ALWAYS POSSIBLE: Healing Rifts among Families, Friends and God

- Cancer Biology Review: A Case-Based Approach

- Physical Foundations of Continuum Mechanics