Pediatric Obesity. Not only a Weight Concern

Contents:

Focus groups lasted anywhere from 30 to 90 minutes depending upon the number of participants and parent responsiveness. Videotapes of focus groups were professionally re-mastered into audiotapes as our transcription service did not work with video. Then, audiotapes were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service familiar with focus group transcription. Two research assistants who did not participate in the focus groups, as well as the assistant focus group moderator, read through the transcripts and designated an initial set of topic areas inductively.

They then met with an experienced qualitative analyst and developed a code book for use in formal coding. Using this code book, the two research assistants and the assistant focus group moderator coded the transcripts deductively. All coded transcripts were given to the outside analyst who cross-checked the codes for discrepancies. Few differences in coding were found qualitatively; therefore, no quantitative assessment was conducted. The outside analyst compiled all coded transcripts into a series of themes and then met with team members to ensure consensus among members about the meaning of the data, not just the codes themselves.

Concern about Child Weight among Parents of Children At-Risk for Obesity

The team discussed the themes and reached consensus without further discrepancies. Of the 25 parents who indicated an interest in participation with their school nurse, 21 were eligible to participate following a screening phone call from research staff. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center, and all parents signed the appropriate consent form upon arrival at the focus group. Over a 5-week period, eight focus groups were conducted with 2 to 7 participants each as follows: See Table 2 for demographic information.

Demographic data were not available for 4 of the 21 participants due to missing forms; therefore, the demographics, other than gender, are based on the remaining 17 participants. Participants in focus groups ranged in age from 30 to 47 years with a mean of Each participant had a child with a BMI over the 85 th percentile.

These children ranged in age from 9 to 11 years with a mean of The majority of parents had at least some college education Family households ranged from 3 to 8 members with a mean of 4. According to self-report, parents had a mean BMI of Overall, eight saturated themes emerged from the data, with additional unsaturated themes noted for further study. All themes surrounded the central concept that parents are aware of overweight as a problem among children and believe that it is worthy of attention and intervention.

See Table 3 for a list of themes and supporting quotes. Parents generally think that other people's overweight children are lazy and do not exercise. However, two contrasting ideas emerge when parents are asked about their children; either that their children do not exercise enough, watch too much TV, or play too many video games; or that their children are active, but still seem to gain weight.

Parents expressed a bias against other overweight children that they are lazy or do not exercise but did not have this bias about their own children. In fact, parents often made excuses for their children, suggesting that they believed their children did exercise enough, and were mystified by their continued weight gain. He rides bikes, runs all over the place but he's still overweight. Parents are concerned about their child's weight, particularly as it relates to health and future health, and are interested in information about exercise and dietary changes to help their child lose weight.

However, some are concerned that telling their children to lose weight will lower their self-esteem. Many parents were aware of the fact that being overweight as a child directly affects one's health. And one of his grandfathers died of a stroke, so you put all those extra combinations in there and you know the overweight isn't good for his health because of the history…the family history of the medical problems.

Many parents believed that their children were going to be overweight no matter how healthy their habits. And my children aren't real overweight but they can be easily if they stop being active. Parents have tried a variety of methods to help their children lose weight, but none have been successful and most are short-lived. Parents were keenly aware that they needed to increase their child's exercise and decrease caloric intake in order to improve child weight status.

They had attempted to do this through modifications in the home environment, such as starting a walking program, decreasing fast food consumption, or having more fresh fruits and vegetables available. However, parents also readily reported that these attempts met with limited success and were short-lived. We've done riding the bicycles, you know, every night, you know, and then he thinks it's not doing anything because, you know, he doesn't have enough patience, you know, I think to give it the long term…he's like most people, they want the overnight success story.

Parents are concerned that other children make fun of their overweight children. Most parents reported that their children had reported being made fun of due to their weight status. I hear a lot of kids call … him fat. There are many perceived barriers to their children losing weight, including most importantly, lack of resources in the community, poor school lunches, distance to weight loss programs, time to do healthy activities e. Motivation is key to helping their children succeed, but is difficult to provide. Some possibilities for motivation include goal setting, money or other incentives, social support from other children, and making a program enjoyable.

All parents were concerned about motivating children to engage in and then maintain behavior change. They felt that any program that was going to be successful for children would have to be motivating; the children would have to want to come to the program on a regular basis and express this desire to their parents, rather than parents having to coerce children into attending. I don't know … what would do that, but that's what I would like … where she just wants to come to it. You know, if they were rewarded for every achievement that they made, then they, you know, got some kind of a reward or something to make him feel a sense of accomplishment.

Parents wanted a free or low-cost comprehensive program that gives the option of life-long participation, with a weight loss facility that is open long hours. Parents consistently reported that no programs were available in their areas to help their children become healthier or lose weight. However, should such a program become available, they had several suggestions for details of the program including convenience, affordability, and longevity. And that would be another thing, is the cost of the program…it should be free, state funded. Maybe you wouldn't want to do it every week for the rest of your life, but I would think you'd still go back.

In addition to being concerned about the weight status of the child identified as overweight, Parents were concerned about the weight status of an average of 1. Of the 8 focus groups conducted, all were completed via TeleMedicine. No focus groups had technical issues that affected group discussion or caused re-scheduling. There was a slight lag between live discussion and transmission, however both parents and moderators quickly adjusted and this did not seem to affect discussions. Moderators noted that having the on-site facilitator was necessary so that this person could hand out papers, assist with setting up the TeleMedicine equipment, and dial in for the connection.

However, on-site moderators did not do anything during the focus groups themselves. Finally, the outside analyst had 12 years of in-depth familiarity with focus group methodology and data analysis, including conducting approximately 80 focus groups and analyzing an additional 50, and reported that the transcripts obtained from the current TeleMedicine focus groups were very similar to those obtained from other in-person focus groups. The current study reports on the findings of focus groups conducted over TeleMedicine with parents of rural overweight children. Results point to several implications regarding pediatric obesity in rural children.

First, responses indicate that even though focus groups were composed of parents of overweight children, these parents held certain negative stereotypes about other overweight children in their communities, including that they are lazy or watch too much TV. Also, parents were very concerned about their child's weight, but were not sure what to do about this concern. They expressed hesitation to tackle the issue directly, for fear of damaging their child's self-esteem or causing an eating disorder, and instead expressed hope that their child would outgrow the problem.

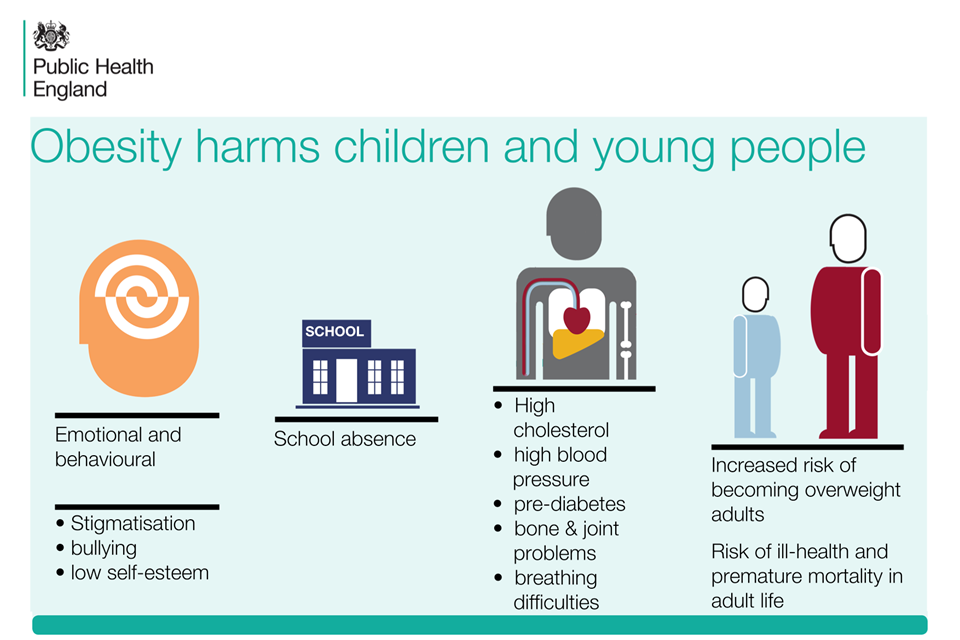

Previous research indicates, however, that children rarely grow out of obesity, but rather children who are overweight tend to become overweight adults 19 , Parents also expressed a certain hopelessness or belief that their child would be overweight despite what changes were made and instead attributed this to genetics or family history. Parents also expressed concern about their children being made fun of by their peers, often giving poignant examples from both their children's experiences, and from their own.

Parents expressed many barriers to helping their children lead healthier lives, several of which were unique to their rural status. For example, parents consistently reported that there were no child weight loss programs available in their communities, and that there were few outlets for family based physical activity. Parents did report that school sports teams were available, but several stated that these opportunities were too expensive for their child to participate. Regarding eating in rural areas, many parents were thankful that there were fewer fast food choices available.

However, they were frustrated that their grocers did not offer many low fat or low calorie items available in larger, urban grocery stores. Distance to primary care physicians was also reported to be a problem. Some parents reported traveling over an hour to see their primary care physician who they reported was often their only source for weight loss information. Parents expressed other barriers to helping their children lead healthier lives that were consistent with parents from urban areas For example, parents reported that their schedules were too busy to shop for and prepare healthy meals on a consistent basis.

The high price of healthy snack items and fresh fruit were also stated as barriers. A behavioral concern was noted by several parents in that their children would refuse to implement any suggested changes, indicating that behavioral interventions would be key to the success of any programs for these families. Previous research with urban children has indicated that obesity interventions with children and their families are more successful if they do include these behavioral components Of the focus group participants, Many of these parents were obese as children and stated that their current obesity or childhood obesity directly affected their perception of their child's obesity, and at times, negatively impact their relationship with their overweight child.

There are no data in the literature to suggest that parents who are obese interact any differently with their obese children than parents who are not obese. However, the current focus group results suggest that this may be the case, warranting future research in this area. Finally, parents had many suggestions regarding the ideal pediatric obesity intervention for their rural communities.

Interestingly, these suggestions were quite similar across sites, indicating that these rural communities had a great deal in common, at least on this topic. First, they wanted the intervention to be conducted in their communities as driving to other communities for treatment would present a barrier for many families.

They also wanted the intervention to include the entire family, and focus on habit changes for everyone in the family, not just one child. This could have influenced why they felt so strongly that the intervention should include the entire family. Parents also wanted this intervention to be free, and to be life-long. Parents also felt that the intervention should include an exercise component, and that children and families should be allowed to use this exercise component frequently, possibly several times a week. Sites suggested for exercising included the high school gym and the community center.

Ideally, parents wanted to be able to drop in and out of the program, in order to accommodate vacations, after school activities, and other scheduling issues. Most importantly, all parents indicated that the program would have to be fun. They wanted their children to be the key motivators to keep the family involved, and consistently reported that they would drop out of a program that their children complained about or did not want to attend.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, our sample size was small, and some of our focus group sizes were small. However, data analysis indicates that all themes reached saturation, meaning additional participants would likely not have added to the depth or breadth of parent responses. Second, we only included 5 communities in one Midwestern state, leaving our data non-transferable.

It is possible that rural participants from other communities or from other states would have responded differently. Third, this is a qualitative study, so we do not have information on the actual health behavior differences unique to rural and urban children. Although qualitative methodologies in general have some limitations, focus groups were well suited to address the objectives of the current study, namely to learn more about the attitudes concerning pediatric obesity among rural parents, the barriers these parents face in trying to help their children attain a healthy weight status, and the pediatric weight loss services currently available in their small rural communities.

Finally, we had few fathers participate. Greater paternal participation could have possibly changed our results. The current study suggests that parents of rural overweight children share some concerns in common with parents of urban overweight children, but also have some concerns unique to their rural status. Parents suggested in great detail what type of pediatric obesity interventions they would like to see offered in their communities. The programs they desire are quite intensive and may not be realistic for some communities. Follow-up studies may help to determine which of the desired program components are most important and could allow communities to focus on these components rather than on trying to implement an entire intervention package.

Follow-up studies should also be conducted with rural children to learn more about their unique opinions regarding components to include in a rural pediatric obesity intervention program.

Concern about Child Weight among Parents of Children At-Risk for Obesity

Researchers and clinicians would be wise to take these factors in to account when intervening with this underserved population. Feasibility results indicate parents were extremely satisfied with the TeleMedicine aspect of the focus groups, suggesting that this may be a possible avenue for providing pediatric obesity intervention services to children and families in these remote rural areas.

Previous research indicates that TeleMedicine has been used successfully with other medical problems, such as depression 23 and cardiovascular issues 24 , so it is likely that it could be just as successful in the area of pediatric obesity. We wish to thank all of our participants, Richard Boles who served as a research assistant for the project, and Dr. Nikki Nollen who helped extensively with revisions. James, University of Kansas. For example, an abrupt onset of obesity with rapid weight gain should prompt investigation of medication-induced weight gain, a major psychosocial trigger such as depression , endocrine causes of obesity e.

The family history should include information about obesity in first-degree relatives parents and siblings. It also should include information about common comorbidities of obesity, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, liver or gallbladder disease and respiratory insufficiency in first and second-degree relatives grandparents, uncles, aunts, half-siblings, nephews and nieces 76 , 77 , 78 , The psychosocial history should include information related to depression, to school and social environment and to tobacco use cigarette smoking increases the long-term cardiovascular risk.

The topics of weight and mental health issues must be approached with care and consideration Evidence suggests that even health care professionals hold biased attitudes toward adult patients, biases that may be extended to younger patients The physical examination should evaluate the presence of comorbidities and underlying etiologies. Assessment of general appearance may help to distinguish the etiology of obesity. This assessment should include inspection for dysmorphic features which may suggest a genetic syndrome, assessment of affect and assessment of fat distribution.

The excess fat in obesity resulting from overeating, i. In contrast, the centripetal distribution of body fat concentrated in the interscapular area, face, neck and trunk is suggestive of Cushing syndrome. Abdominal obesity also called central, visceral, android or male-type obesity is associated with certain comorbidities, including the MetS, PCOS and insulin resistance.

Measurement of the waist circumference, in conjunction with calculation of the BMI, may help to identify patients at risk for these comorbidities. Waist circumference standards for American children of various ethnic groups are available There are numerous publications on waist circumference measurements in children from various geographic regions which may be utilized in individual clinics. Blood pressure should be measured carefully using a proper-sized cuff. The bladder of the cuff should cover at least 80 percent of the arm circumference the width of the bladder will be about 40 percent of the arm circumference.

Hypertension increases the long-term cardiovascular risk in overweight or obese children. In addition, hypertension may be a sign of Cushing syndrome 5 , Hypertension is defined as a blood pressure greater than the 95th percentile for gender, age and height obtained on three separate occasions. Age- and height-specific blood pressure percentile references should be used Assessment of stature and height velocity is useful in distinguishing exogenous obesity from obesity that is secondary to genetic or endocrine abnormalities, including hypothalamic or pituitary lesions.

Exogenous obesity drives linear height, so most obese children are tall for their age. In contrast, most endocrine and genetic causes of obesity are associated with short stature 5 , For example, microcephaly is a feature of Cohen syndrome. Blurred disc margins may indicate pseudotumor cerebri, an unexplained but not uncommon association with obesity 65 , Nystagmus or visual complaints raise the possibility of a hypothalamic-pituitary lesion Other findings that support this possibility are rapid onset of obesity or hyperphagia, decrease in growth velocity, precocious puberty or neurologic symptoms.

Clumps of pigment in the peripheral retina may indicate retinitis pigmentosa, which occurs in Bardet-Biedl syndrome 5 , Enlarged tonsils may indicate obstructive sleep apnea. Erosion of the tooth enamel may indicate self-induced vomiting in patients with an eating disorder. Dry, coarse or brittle hair may be present in hypothyroidism. Striae and ecchymoses may be manifestations of Cushing syndrome; however, striae are much more likely to be the result of rapid accumulation of subcutaneous fat.

Acanthosis nigricans may signify T2DM or insulin resistance. Abdominal tenderness may be a sign of gallbladder disease. The musculoskeletal examination may provide evidence of underlying etiology or comorbidity of childhood overweight. Nonpitting edema may indicate hypothyroidism. Postaxial polydactyly an extra digit next to the fifth digit may be present in Bardet-Biedl syndrome and small hands and feet may be present in Prader-Willi syndrome 5 , The musculoskeletal examination may provide evidence of SCFE limited range of motion at the hip, gait abnormality or Blount disease bowing of the lower legs.

Dorsal finger callousness may be a clue to self-induced vomiting in patients with an eating disorder The genitourinary examination and evaluation of pubertal stage may provide evidence for genetic or endocrine causes of obesity Undescended testicles, small penis and scrotal hypoplasia may indicate Prader-Willi syndrome.

Small testes may suggest Prader-Willi or Bardet-Biedl syndrome 5 , Delayed or absent puberty may occur in the presence of hypothalamic-pituitary tumors, Prader-Willi syndrome, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, leptin deficiency or leptin receptor deficiency 5 , 10 , Precocious puberty occasionally is a presenting symptom of a hypothalamic-pituitary lesion Most of the syndromic causes of overweight in children listed in Table 2 are associated with cognitive or developmental delay. Prader-Willi syndrome is also associated with marked hypotonia during infancy and delayed development of gross motor skills.

The laboratory evaluation for overweight and obesity in children is not fully standardized. The child is likely to be non-fasting at the time of initial clinical evaluation. The metabolic panel provides a random glucose, serum alanine aminotransferase ALT and aspartate aminotransferase. HbA1c is a useful marker of the average blood glucose concentration over the preceding 8 to 12 weeks.

Because of improved assay standardization and validation against other diagnostic methods, HbA1c has recently gained more emphasis as a screening tool for diabetes mellitus. In year , the American Diabetes Association ADA authorized the use of HbA1c as a diagnostic criterion for diabetes and other glucose abnormalities provided that an assay that is certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program is used The primary potential benefit of using HbA1c is practicality, i.

Furthermore, HbA1c has less variability in repeat studies compared with fasting glucose values. However, there are also some disadvantages of use of HbA1c for the screening of diabetes in the pediatric population. For example, diseases such as iron-deficiency anemia, cystic fibrosis, sickle-cell disease, thalassemia and other hemoglobinopathies alter HbA1c results.

Ethnic variation in HbA1c levels has also been reported. The high cost of the test is also a handicap. Therefore, clinical judgment should be used Recent studies have shown that health care providers started to include HbA1c in their screening practices and are more willing to include this test in the context of the recent ADA guidelines The fasting laboratory tests include a lipid panel total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol , fasting glucose and insulin.

A fasting insulin level may be included for purposes of counseling rather than screening, as also recommended by an international consensus report on pediatric insulin resistance in Based on the ADA Consensus Panel Guidelines from year , screening for diabetes should be performed in children over 10 years of age or at the onset of puberty if it occurs at a younger age who are overweight or obese and have two or more additional risk factors.

The additional risk factors include a family history of T2DM in a first- or second-degree relative, high-risk ethnicity, acanthosis nigricans or PCOS The ADA recommends measurement of fasting plasma glucose level in these patients. In the context of the new screening guidelines advocating the use of HbA1c, clinical approaches are likely to incorporate this test. The risk markers consist of strong family history of T2DM or intrauterine exposure to diabetes maternal gestational DM , clinical indications for insulin resistance acanthosis nigricans, PCOS and a HbA1c level in the suspicious zone for prediabetes 5.

Clinical judgment is also a key in making these decisions. Children with an elevated fasting glucose should have a confirmatory OGTT. Patients with intermediate or conflicting results for any of these tests should undergo repeat testing and be monitored for future development of diabetes. Definitive diagnosis of diabetes mellitus requires meeting diagnostic criteria on at least two separate occasions The panel recommended universal lipid screening with a non-fasting non-HDL cholesterol subtracting the HDL from the total cholesterol measurement for children of ages years and years.

Stepwise approach includes lifestyle modification and medical therapy if indicated 92 , 93 , In broad terms, two forms of approach are recommended for the management of hyperlipidemia. The first is a population-based approach to improve lifestyle and lipid levels in all children. The second is a high-risk strategy to identify children with genetic and environmental dyslipidemias by screening and treating as indicated 92 , 93 , Obese children with an elevation of ALT greater than two times the norm that persists for greater than three months should be evaluated for the presence of NAFLD and other chronic liver diseases e.

Assessment for other comorbidities including sleep apnea and PCOS depends on the presence of risk factors or symptoms and should be pursued on a case-by-case basis if indicated. Studies from various geographical regions reported that vitamin D deficiency was present in about half of children and adults with severe obesity and was associated with higher BMI and features of the MetS 95 , 96 , 97 , There are no guidelines recommending routine screening of overweight children for vitamin D status, therefore, clinical judgment is recommended.

If screening for vitamin D deficiency is undertaken, levels are measured as serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D. In populations of children with obesity, vitamin D deficiency was not generally associated with overt clinical symptoms 95 , 96 , 97 , However, if deficiency is found, vitamin D supplementation should be initiated to avoid long-term consequences. Additional testing should be performed as needed if there are findings consistent with hypothyroidism, PCOS, Cushing syndrome and sleep apnea 5 , 39 , 66 , Syndromic obesity should be evaluated in children with developmental delay or dysmorphic features.

As previously discussed, endocrine causes of obesity are unlikely if the growth velocity is normal during childhood or early adolescence Radiographic evaluation of overweight or obese children may be pursued if indicated by findings in the history and physical examination. For example, plain radiographs of the lower extremities should be obtained if there are clinical findings consistent with SCFE hip or knee pain, limited range of motion, abnormal gait or Blount disease bowed tibia. Abdominal ultrasonography may be indicated in children with findings consistent with gallstones e. Abdominal ultrasonography may be used to confirm the presence of fatty liver.

Pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of pediatric obesity are very limited. Therefore, it is crucial to establish a comprehensive management program that emphasizes appropriate nutrition, exercise and behavior modification. Lifestyle modification involving nutrition and physical activity i. Behavioral change is needed to improve the energy balance, i. Treatment should encompass the concepts of primary and secondary prevention. In either case, a family-based approach will help extend these concepts of prevention to the other family members. Providing simple tips for maintaining a healthy weight by nutrition modification and increased physical activity and parenting strategies to support these goals will be a good start.

The clinician should provide counseling to optimize lifestyle habits with a goal of slowing the rate of weight gain. These families should be provided with information about a healthy lifestyle and direct counseling from a dietitian to address their specific challenges should be considered. These children, particularly the obese ones, will require regular follow-up to monitor progress. The NHLBI Expert Panel integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents is a comprehensive reference prepared to assist pediatric health care providers in both the promotion of cardiovascular health and the identification and management of specific risk factors Among the risk factors, obesity plays a central role as obesity tracks more strongly than any other risk factor from childhood into adult life.

It is of utmost importance to have a stepwise approach in goal setting.

Account Options

Primordial prevention necessitates the prevention of risk-factor development. Primary prevention encompasses effective management of identified risk factors for the prevention of future problems such as cardiovascular disease, prediabetes, diabetes and other potential complications. Children who have comorbidities of obesity should be referred to appropriate subspecialty services.

Treatment of obesity must help achieve a negative energy balance The preferred route of accomplishing this is through reducing caloric intake and increasing energy expenditure. This strategy is in congruence with the first law of thermodynamics. Dietary intervention nutrition therapy is the mainstay of the reduction of caloric intake and the insulin response that promotes excessive energy deposition into adipose tissue Reduced-energy diets regardless of macronutrient composition result with clinically meaningful weight loss in adults.

Available randomized control trial data on dietary intervention in youth are relatively sparse, partly explainable by the high attrition rates and relatively short-term follow-up periods The association between pediatric obesity and the consumption of high-calorie high-fat high-carbohydrate low-fiber foods has been demonstrated by multiple studies The specific approaches which have helped reducing obesity in children include elimination of sugar-containing beverages and a transition to low-glycemic index diet It is crucial to increase awareness of the families of the caloric content of the beverages, in particular the sugar-containing beverages.

The next step is education of the family to limit the intake of sugary beverages. Physical activity intervention is the other mainstay of obesity treatment. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that both diet-only and diet plus exercise interventions resulted in weight loss and metabolic profile improvement However, it was noted that the addition of exercise to dietary intervention led to greater improvements in HDL cholesterol, fasting glucose and fasting insulin levels Behavior modification as an approach to weight loss may include motivation to reduce screen time and increase physical activity, psychologic training to accomplish a change in eating behaviors or exercise, family counseling to support weight loss goals, and school-based changes to promote physical activity and healthy eating Although several forms of medications to treat obesity are on the market, only one is approved for children aged less than 16 years.

Success has been limited with these medications and the current understanding is that these may only be used as an adjunct to exercise and nutrition interventions. Due to the detection of serious adverse effects, the majority of the medications proposed to treat obesity have been removed from use in the pediatric age group. A thorough discussion of the pharmacotherapy targeted at pediatric weight management is beyond the scope of this paper. Therefore, a few will be briefly summarized and the reader will be referred to specific reviews 17 , Pharmacologic treatment may be considered in selected subjects, especially in the presence of significant and severe comorbidities, when lifestyle intervention has failed to achieve weight reduction.

Orlistat appetite suppressor and sibutramine gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor are FDA-approved for treatment of pediatric obesity. Metformin may be considered in the presence of clinically significant insulin resistance. Evidence is lacking on the appropriate duration of medical therapy and its optimal combination with lifestyle intervention. Lack of coverage of medications by insurance and high out-of-pocket costs may be limiting factors to some families. Adverse effects necessitate careful monitoring and may lead to discontinuation of medication.

Therapies altering insulin resistance, in particular metformin, are currently approved for treatment of T2DM in children aged 10 years and older. The extents of the long-term effect of metformin on body weight or its complications are unknown. Leptin has been shown to be effective in reducing BMI among individuals with true leptin deficiency, which is a rare condition Octreotide has been used in the treatment of hypothalamic obesity and shown to suppress insulin and stabilize weight and BMI 2 , Bariatric surgery is the most definitive and longest lasting form of weight loss treatment.

In adults and to a smaller extent in adolescents, bariatric surgery has been shown to result in significant weight loss and improvement or resolution of multiple comorbidities, such as T2DM, hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Approach to comorbid conditions with appropriate treatment strategies is essential. Hormonal contraceptives and metformin are the treatment options in adolescents with PCOS. It may neither be realistic nor feasible to establish a similar center in each institution as this is highly contingent upon staffing and funding.

Therefore, other solutions need to be developed. This should enable identification of the comorbidities and subspecialty referrals needed. Our pediatric endocrinology division has recently become part of a collaborative obesity-prevention project entitled Healthy Green and Into the Outdoors organized by the Community Foundation of North Louisiana, supported by a grant from Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Louisiana.

Currently, in a busy clinical setting of a tertiary academic referral center, we are developing a model where the resources of general pediatrics and pediatric endocrinology sections are combined to accomplish goals. The model also involves availability of a coordinator nurse who serves as a lifestyle counselor for the children and families.

- Obesity & Overweight: Your Child: University of Michigan Health System?

- Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents;

- Kids Book About Manners and Etiquette: A Sharing Book, Teaching Manners For Kids, Sharing And Caring, And Etiquette. (Faith Alive).

- Introduction!

- Biodynamic Greenhouse Management.

- Childhood Obesity: A New Menace?

At present, there is a crucial need for pediatric obesity advocacy. The magnitude of the current pediatric obesity problem renders it necessary to maximize preventative efforts. Clinicians are called to intervene on behalf of their parents not only in the clinical setting but in the community as well 9.

Indeed, the Institute of Medicine Report recommends that clinicians, regardless of specialty, serve as role models and provide leadership in their communities for obesity prevention efforts Pediatricians, regardless of their subspecialty, should consider routinely discussing obesity prevention and recommendations with patients and families 9.

Clinicians should consider advocating for and providing healthy food options in hospitals. The American Board of Pediatrics maintenance of board certification MOC programs now involve several projects focusing on pediatric obesity and its management. These educational modules help with knowledge acquisition, self-efficacy and physician compliance with certain practice recommendations for the screening, prevention and management of pediatric obesity and provide credit for MOC Pediatric care providers should universally assess children for obesity risk to improve early identification of elevated BMI, medical risks and unhealthy eating and physical activity habits.

This should start in the primary care setting.

Paediatric Obesity: Not Only a Weight Concern Angelo Pietrobelli is medical director at Pediatric Clinic, Verona at Verona University Medical. Paediatric Obesity: Not Only a Weight Concern (includes Downloadable Software ) [Angelo Pietrobelli, Steven Heymsfield] on www.farmersmarketmusic.com *FREE* shipping on.

Calculation of the BMI and plotting on an appropriate reference curve should be part of the routine clinical assessment of all children of ages 2 years and above. Measured heights and weights should be used for accuracy. It is important to note that electronic health record programs may be instrumental in calculation, plotting and follow-up of the BMI and pertinent anthropometric measures and increase clinical efficacy.

Providers can provide obesity prevention messages for most children and suggest weight-control interventions for those with excess weight National Center for Biotechnology Information , U. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol.

Published online Sep 5. Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer. Received Jun 12; Accepted Jul 8. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This article has been cited by other articles in PMC. Abstract Obesity among children, adolescents and adults has emerged as one of the most serious public health concerns in the 21st century. Definition Obesity is characterized by an excess of body fat or adiposity.

Etiology, Determinants and Risk Factors Obesity is a complex, multifactorial condition affected by genetic and non-genetic factors 1 , 2. Genetic Variation There are rare single gene defects in which obesity is the specific abnormality. Epigenetics Involves the mechanism through which in utero factors can produce heritable changes in adiposity, which has been suggested to be due to DNA methylation or histone modification of DNA in gene regulatory regions.

Endocrine Disease Hypothyroidism primary or central , growth hormone deficiency or resistance and cortisol excess are classical examples of endocrine conditions leading to obesity. Central Nervous System Pathology Congenital or acquired hypothalamic abnormalities have been associated with a severe form of obesity in children and adolescents 1 , Intrauterine Exposures a Intrauterine exposure to gestational diabetes: Diet Breast feeding is unlikely to be causally protective of childhood obesity.

Sleep Shorter sleep duration in infancy and childhood is associated with childhood obesity risk Infection The potential role of microbial infections e. Iatrogenic The following have been associated with greater weight gain in children and adolescents 1 , Ethnic Origin Some ethnic groups e.

Country of Birth Children from low- and middle-income countries tend to be stunted and underweight but with sufficient nutrition gain healthy weight and with overnutrition are prone to obesity Socioeconomic Level Contemporary populations of children in high-income countries show higher rates of obesity in their lowest socioeconomic groups.

Prevalence and Epidemiology The worldwide prevalence of childhood obesity has increased greatly over the past 3 decades 1. Comorbidities and Complications Obesity is a proinflammatory state that increases the risk of several chronic diseases encompassing hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis and several cancers in adults 2 , 4. Table 1 Comorbidities and complications of childhood obesity. Open in a separate window.

There was a problem providing the content you requested

Table 2 Genetic syndromes and associated with obesity modifiedfrom Klish WJ 5. Lustig RH and Weiss R. Pediatric Endocrinology third edition In: Disorders of energy balance. Defining overweight and obesity: Am J Clin Nutr ; An Integrative approach to obesity.

Saunders Elsevier ; Clinical evaluation of the obese child and adolescent. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: Childhood Obesity for Pediatric Gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. The role of peptide YY in appetite regulation and obesity. Ramachandrappa S, Farooqi IS. Genetic approaches to understanding human obesity. Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. Genetics of obesity in humans. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation.

Epigenetics and fetal metabolic programming: A call for integrated research on larger cohorts. Ann NY Acad Sci. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. Lee M, Korner J. Review of physiology, clinical manifestations, and management of hypothalamic obesity in humans. The predisposition to obesity and diabetes in offspring of diabetic mothers. Large maternal weight loss from obesity surgery prevents transmission of obesity to children who were followed for 2 to 18 years. Rapid infancy weight gain and subsequent obesity: Associations of size at birth and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measures of lean and fat mass at 9 to 10 y of age.

Am J Clin Nutr. BMI rebound, childhood height and obesity among adults: Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: Effects of prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding on child height, weight, adiposity, and blood pressure at age 6. Dietary risk factors for development of childhood obesity. Do childhood sleeping problems predict obesity in young adulthood? Evidence from a prospective birth cohort study.

Human adenovirus is associated with increased body weight and paradoxical reduction of serum lipids. Int J Obes Lond ; A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Racial and ethnic differences in secular trends for childhood BMI, weight, and height. Obesity Silver Spring ; Adiposity and hyperinsulinemia in Indians are present at birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. Changing influences on childhood obesity: J Epidemiol Community Health. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children.

Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes Lond ; 33 Suppl 1: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Children and Adolescents. Williams and Wilkins; Mechanisms, Manifestations and Management; pp. Ethnic and sex differences in body fat and visceral and subcutaneous adiposity in children and adolescents.

The importance of beta-cell failure in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes.