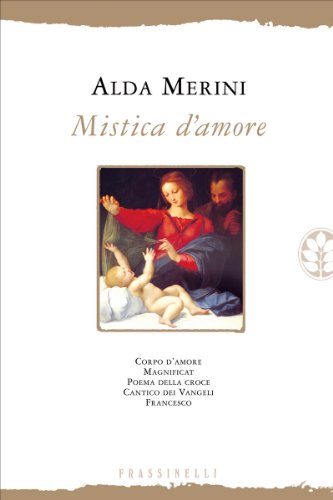

Domenica sera (I canguri) (Italian Edition)

Contents:

Enter your mobile number or email address below and we'll send you a link to download the free Kindle App. Then you can start reading Kindle books on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required. To get the free app, enter your mobile phone number. Would you like to tell us about a lower price? Read more Read less. Kindle Cloud Reader Read instantly in your browser. Product details File Size: Feltrinelli Editore October 18, Publication Date: October 18, Sold by: Not Enabled Enhanced Typesetting: Enabled Amazon Best Sellers Rank: Share your thoughts with other customers.

Even if the ST word has entered the TL as a loan-word e. These losses will virtually never matter, of course. In many contexts, this translation loss could well matter rather a lot. In the opposite sort of case, where the ST contains a TL expression e. As these examples suggest, it is important to recognize that, even where the TT is more explicit, precise, economical or vivid than the ST, this difference is still a case of translation loss. It is certainly true that the following TTs, for example, can be said to be more grammatically economical, sometimes even more elegant and easier to say, than their STs.

There is no need to give examples just now: For the moment, all we need do is point out that, if translation loss is inevitable, the challenge to the translator is not to eliminate it, but to control and channel it by deciding which features, in a given ST, it is most important to respect, and which can most legitimately be sacrificed in respecting them. The translator has always to be asking, and answering, such questions as: Does it matter if an intralingual TT of the extract from Macbeth on p. There is no once-and-for-all answer to questions like these. Everything depends on the purpose of the translation and on what the role of the textual feature is in its context.

Sometimes a given translation loss will matter a lot, sometimes little. Whether the final decision is simple or complicated, it does have to be made, every time, and the translator is the only one who can make it. Discuss the strategic decisions that you have to take before starting detailed translation of this ST, and outline and justify the strategy you adopt. Number these points in the TT and in iii , as you did in Practical 1.

Contextual information The text is taken from a glossary of Soviet and Russian terms that have become part of the Italian language. The glossary is over pages long, and is as much an introduction to recent history as it is an essay in lexicography. NB Misprints in the original have been corrected here. ST a Contextual information. The text is a proverb. ST b Contextual information. A trainload of deportees has just got out onto the platform. General cultural differences are sometimes bigger obstacles to successful translation than linguistic differences.

The chapter is based on comparison of certain features of the following ST and TT. Lei ha scelto le Compliments! Le Blackpool, calzature di fine The Blackpool, shoes of fine lavorazione, vengono eseguite con la manufacturing are executed with the stessa particolare cura dei vecchi same particular care of the old ciabattini.

The TT is rich in translation loss! This loss is mostly lexical and grammatical. We will just look at four cases which are good examples of loss arising from differences in cultural expectations between ST public and TT public. Doubtless the name was chosen to give the shoe a touch of foreign chic. If this loss matters to the manufacturer, two alternatives suggest themselves. If we pause for a moment to look at this question, it will prove a useful introduction to the cultural dimension of translation.

There are two main alternatives in dealing with names.

Assuming that the name is an SL name, the first alternative introduces a foreign element into the TT. This loss will not usually matter. More serious is the sort of case where using the ST name introduces into the TT different associations from those in the ST. Brand names are a typical danger area. Italian sales may be enhanced by the footballing connotations, but the English connotations are completely inappropriate.

Translating an Italian ST in which someone washed down a pot of Mukk yoghurt with a glass of Dribly, one would have to drop the brand names altogether, or perhaps invent English ones with more product-enhancing associations.

Domenica sera (I canguri) (Italian Edition) - Kindle edition by Marco Drago. Download it once and read it on your Kindle device, PC, phones or tablets. Domenica sera (I canguri) (Italian Edition) eBook: Marco Drago: www.farmersmarketmusic.com: Kindle Store.

Simply using the ST name unchanged in the TT may in any case sometimes prove impracticable, if it actually creates problems of pronounceability, spelling or memorization. This is the standard way of coping with Russian and Chinese names in English texts. There is a good example in the text in Practical 2.

When the disaster happened, of course, few in the West had heard of Chernobyl, and the first Western correspondents had to devise their own transcriptions. However, once a TL consensus had emerged, there was little choice: This is normal practice; the translator simply has to be aware that standard transliteration varies from language to language and is common in the translation of place names: Some names do not need transliteration at all, but have standard TL equivalents.

The same applies to initials and acronyms: Keeping the Italian form here would normally introduce needless obscurity and undermine confidence in the translator. The second example we want to look at is the reference to slaughterhouses. Although leather shoes are all made from animals that have been killed, people in the United Kingdom do not on the whole like to be reminded of this, just as they are often reluctant to eat small birds, or little animals like rabbits that have not been dismembered to stop them looking like little animals. Italians are by and large less squeamish about such things.

In other words, the lexical translation loss is a lesser evil here than serious consumer resistance would be. The other two examples of loss arise from another sort of cultural difference. We shall use the general term cultural transposition for the main types and degrees of departure from literal translation that may be resorted to in the process of transferring the contents of an ST from one culture into another.

The result is to reduce foreign features in the TT, thereby to some extent naturalizing it into the TL and its cultural setting. The various degrees of cultural transposition can be visualized as points along a scale between the extremes of exoticism and cultural transplantation: Exoticism and calque The extreme options in signalling cultural foreignness in a TT fall into the category of exoticism.

A TT marked by exoticism is one which constantly uses grammatical and cultural features imported from the ST with minimal adaptation, thereby constantly signalling the exotic source culture and its cultural strangeness. A TT like this, however, has an impact on the TL public quite unlike any that the ST could have had on an SL public, for whom the text has fewer features of a different culture.

Even where the TT as a whole is not marked by exoticism, a momentary foreignness is sometimes introduced in the form of calque. A calque is an expression that consists of TL words and respects TL syntax, but is unidiomatic in the TL because it is modelled on the structure of an SL expression. This lack of idiomaticity may be purely lexical and relatively innocuous, or it may be more generally grammatical. The following calques illustrate decreasing degrees of idiomaticity: Chi dorme non piglia pesci. He who sleeps catches no fish. In his house each is king.

Le Blackpool vengono eseguite con la The Blackpool are executed with the stessa particolare cura dei vecchi same particular care of the old ciabattini. For most translation purposes, it can be said that a bad calque imitates ST features to the point of being ungrammatical in the TL, while a good one compromises between imitating ST features and offending against TL grammar. It is easy, through haste or ignorance, to mar the TT with bad calques. We shall return to this point in a moment, when looking at communicative translation. Sometimes, what was originally a calqued expression actually becomes a standard TL cultural equivalent of its SL original.

Cultural transplantation At the other end of the scale from exoticism is cultural transplantation, whose extreme forms are hardly translations at all, but more like adaptations—the wholesale transplanting of the entire setting of the ST, resulting in the entire text being completely rewritten in a target-culture setting. Hollywood remakes of European films are familiar cases of this.

Cultural transplantation on this scale is not normal translation practice, but it can be a serious option, especially in respect of points of detail—as long as they do not have knock-on effects that make the TT as a whole incongruous. By and large, normal translation practice avoids the two extremes of exoticism and cultural transplantation. In avoiding the two extremes, the translator will consider the alternatives lying between them on the scale given on p. This is termed cultural borrowing.

It introduces a foreign element into the TT. Of course, something foreign is by definition exotic; this is why, when the occasion demands, it can be useful to talk about exotic elements introduced by various translation practices. But cultural borrowing is different from exoticism as defined above: Translators often turn to cultural borrowing when it is impossible to find a suitable indigenous TL expression. As with calque, such borrowings sometimes become standard TL terms—think of all the Italian musical terms that entered English in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Cultural borrowing only presents the translator with a true choice in cases where previous translation practice has not already firmly established the ST expression in the TL. However, caution needs to be exercised in translating SL words that have become TL loan-words, because they often have more meanings in the SL than in the TL, and sometimes even have a different meaning in the TL from their SL one. Communicative translation As we saw on p.

Only special contextual reasons could justify not choosing communicative translation in such cases as the following: Magro come un chiodo. As thin as a rake. Literal translation of expressions like these would introduce a potentially comic or distracting foreignness not present in the ST.

Sometimes, however, the obvious communicative equivalent will not be appropriate in the context. Each of these has its own connotations; which—if any—is appropriate will depend on what nuance is required in the context. In cases like these, the translator has a genuine choice between literal translation and some degree of communicative translation. It is nearly midday, and hot and stuffy in the classroom.

Gianluca is gazing vacantly out of the window. The teacher rebukes him and, wagging a finger, sententiously quotes the proverb: But in this case it does not work. For one thing, it is practically noon, so that earliness does not come into it. The teacher is telling Gianluca to pay attention, not to leap out of bed and tackle a job that is waiting to be done. It is conceivable, of course, that in certain situations the TL proverb would overlap with the Italian one and be usable in the context—say, if a parent is getting a sleepyhead out of bed. Literal translation is one possibility: Whether these effects were acceptable would depend on the context.

If that were the case, one might keep the literal translation, but add a clause to make it clear that the teacher is quoting an existing proverb and not making one up: It is easy to be misled by semantic resemblances between SL and TL expressions, especially in respect of proverbs. Che 5 trionfino le carni e i pesci. In omaggio alla nobile tradizione zoofila, la gentebene di Britannia dimostra, ancora una volta, di amare gli animali. Anche a tavola, e ben cotti. Questo timido, buffo, simpatico animale erbivoro, che finora aveva saltato e 15 sono salti di nove metri di lunghezza per tre di altezza!

Works (48)

Caro, mite canguro, ti confesso di non essere vegetariano. Eppure mi disturba sapere che anche tu puoi finire nello stomaco degli umani e nelle scatole per gatti. To see what is meant by this, we can return to Gianluca and the teacher pp. Depending on the purpose of the TT, these two effects could be instances of serious translation loss, a significant betrayal of the ST effects. This procedure is a good example of compensation: Translators make this sort of compromise all the time, balancing loss against loss in order to do most justice to what, in a given ST, they think is most important.

Our aim in this book is to encourage student translators to make these compromises as the result of deliberate decisions taken in the light of strategic factors such as the nature and purpose of the ST, the purpose of the TT, the nature and needs of the target public, and so on. In taking these decisions, it is vital to remember that compensation is not a matter of putting any old fine- sounding phrase into a TT in case any weaknesses have crept in, but of countering a specific, clearly defined, serious loss with a specific, clearly defined, less serious one.

Compensation illustrates better than anything else the imaginative rigour that translation demands. The following examples will show some of the forms it can take. Lei ha scelto le Congratulations! In this TT, there are two features that highlight the uniqueness of the new shoes: From the point of view of literal meaning, these expressions are unnecessary departures from the TL structures indicated by the ST grammar: This compensation has also been calculated to fit in with the implications of another one.

Note that none of these departures from literal translation has been forced on the translator by the constraints of TL grammar. This question of choice versus constraint is vital to the understanding of compensation, as we shall see. But is it worth spending time working out how to compensate for this loss? As always, before deciding whether to compensate for a loss, the translator has to ask what the function of the ST feature is in the context.

And the stress on the provenance of the skins perhaps reinforces the impression of authenticity cf. Whatever the translator thinks of this hype, it is there in the ST, and it has a commercial purpose. Here is one possibility: It therefore retains an allusion to where the leather has come from, and implies the realities of slaughter and flaying without naming them. This change of place, and the grammatical change, are also very common in compensation. Like any structural change, all these changes are by definition instances of translation loss.

But, as with the previous example, the point is that they are not forced on the translator by the constraints of TL grammar: It is this deliberateness and precision that makes them into compensation rather than simply examples of standard structural differences between SL and TL. Yet the reference to traditional craftsmen is vital in the ST. Omitting it would mean serious translation loss. Luckily, literal meaning in the ST is again subservient to the commercial blarney, which makes it easier to compensate for this loss: Le Blackpool, calzature di fine Your new shoes are proof positive lavorazione, vengono eseguite con la that the old traditions of skilled stessa particolare cura dei vecchi craftsmanship still flourish in Italy.

This TT is a good example of how compensation can be relatively complex in even the simplest-looking TTs. This loss primarily concerns the ST implications of traditional skill and perfectionism, as we shall see. The image is different from the ST implications of a new performance of a masterpiece.

But, like the ST, the TT is dealing not in rational argument, but in emotive connotations. What the two sets of connotations have in common is the continuing vigour of a creative tradition. It does, however, introduce a different viewpoint from the ST expression: Despite the change, the global message is the same: Compensation is also required on the level of sentence structure in this final paragraph. Ideally, the translator will want to ensure a similar effect in the TT.

But calquing the parenthetical ST structure e. In this way, the rhetorical impact of the TT is similar to that of the ST, but it is achieved by different means. If this phrase is translated literally, the result is a comic calque. Before translating the phrase, the translator has to pin down its function. Stylistically, however, there is another reason for adding these words: We shall suggest three.

Publisher Series by cover

Remember, however, that most cases of compensation belong in more than one category. The most important thing is not to agonize over what label to give an instance of compensation, but to be clear what loss it compensates for and how it does so. Remember, too, that the question of how to compensate can never be considered in and for itself, in isolation from other crucial factors: Compensation is needed whenever consideration of these factors confronts the translator with inevitable, but unwelcome, compromise.

Simply put, it is a less unwelcome compromise. It usually entails a difference in mode between the ST textual effect and the TT textual effect. This compensation in mode can take very many forms. For instance, it may involve making explicit what is implicit in the ST, or implicit what is explicit.

Literal meaning may have to replace connotative meaning, or vice versa. Compensation may involve substituting concrete for abstract, or abstract for concrete. It nearly always involves using different parts of speech and syntactic structures from those indicated by literal translation. In other texts, the same approach may result in replacing, say, a snatch of Dante with an analogous snatch of Milton. An ST pun may have to be replaced with a different form of word play. All these sorts of substitution may be confined to single words, but they more usually extend to whole phrases, sentences, or even paragraphs.

Sometimes, a whole text is affected. For instance, quite apart from lexical and grammatical considerations, if a poem is heavily marked by rhyme and assonance, and the translator decides that for some reason rhyme and assonance would lead to unacceptable translation loss, compensation might consist of heavily marking the TT with rhythm and alliteration instead.

Compensation also usually entails a change in place, the TT textual effect occurring at a different place, relative to the other features in the TT context, from the corresponding textual effect in the ST context. We shall call this compensation in place. We shall call this compensation by splitting. The following sentence, from an unpublished essay by the composer Luca Francesconi, provides an excellent example of the need for compensation by splitting: In such cases, the translator simply has to choose the right term.

But in many other contexts, including this one, it means several of these things at once. There is no single English word that can carry these same combinations of meanings. This is where compensation by splitting comes in. On the contrary, the brutal impression is that there is a wish to do away with anything that is not escapism, including of course research in and through music—that is, above all, a search, an indefatigable quest for founding values, linguistic and human.

A quest that brings with it, for better or for worse, the great and ancient heritage of Western thought. Note that, as happens more often than not, this compensation by splitting also entails grammatical transposition—that is, there is also an element of compensation in mode. There are three instances of this. This complex example raises very clearly the issue of the parameters of compensation. What we have done is deliberately introduce loss in economy and grammar in order to avoid more serious loss in message content. In deciding whether the changes introduced amount to compensation, the crucial factor is the role of context.

If an ST expression has a standard TL counterpart that, regardless of context, spreads it over a relatively longer stretch of TT, then this is a constraint, an instance of canonic expansion, not of compensation. It does reflect lexical differences between Italian and English, but our expansion is not canonic or predictable; in fact it is virtually unrepeatable. Distinguishing the three sorts of compensation is a rough-and-ready categorization.

Each could be refined and subdivided. In any case, most cases of compensation involve more than one category. However, our purpose here is not to elaborate a taxonomy, but simply to alert students to the possibilities and mechanisms of compensation. In fact, in the case of compensation in mode and compensation in place, it is not usually even necessary to label them as such, because virtually all compensation entails difference in mode and place.

The most important lesson to be learned from this chapter is that compensation is a matter of choice and decision. It is the reduction of an unacceptable translation loss through the calculated introduction of a less unacceptable one. Or, to put it differently, a deliberately introduced loss is a small price to pay if it is used to avoid the more serious loss that would be entailed by conventional translation of the expression concerned. So where there is no real choice open to the translator, the element of active compensation is minimal. The easiest way of illustrating this is to look at communicative translation.

Communicative translation does certainly involve compensation, in that it reduces translation loss by deploying resources like those mentioned in the previous paragraph. Certainly, ever since then, translators confronted with this proverb have had to be alert enough to recognize the need for communicative translation—to that extent, producing the TL equivalent does, like all translation, involve choice and decision. But in cases like this one, the translator is not required to devise the TT expression from scratch.

Therefore, in discussing TTs, such cases are generally more usefully noted as communicative translation than analysed as instances of compensation. The same is true of the myriad cases where the canonic literal translation involves grammatical transposition.

- Product details.

- Similar authors to follow?

- .

So preserving TL idiomaticity does in a way compensate for the loss of the ST grammatical structures. But this compensation is even more automatic than that involved in communicative translation. In so far as the canonic literal translation is unavoidable, little choice is involved, and there is no point in discussing such cases as examples of compensation. In both these sorts of mandatory translation, then, the only element of choice is in the decision not to depart from the standard rendering. Occasionally, however, there may be a case for departing from the norm to some extent.

This more often happens with communicative translation than with canonic literal translation. Compensation, then, is a matter of conscious choice, and is unlikely to be successful if inspiration is not allied with analytical rigour. So, before deciding on how to compensate for a translation loss, it is best to assess as precisely as possible what the loss is and why it matters both in its immediate context and in the ST as a whole. This reduces the likelihood of inadvertently introducing, somewhere in the TT, more serious translation losses than the one that is being compensated for.

Say why you think the compensation is successful or unsuccessful; if you think it could be improved, give your own translation, and explain why you think it is better. Give your own translation of these cases, and explain why you think it is better. Pin, a young apprentice, lives in the rough part of a small town on the Ligurian coast. He associates with the drinkers in a local bar, who like getting him to sing lurid or earthy adult songs.

He acts tough by smoking and drinking, but still has not learned to enjoy either. When this episode occurs, Pin is exchanging banter with the men sitting drinking at tables in the bar. ST Gli altri ridono a gola spiegata e lo scappellottano e gli versano un bicchiere. Il vino non piace a Pin: Pin canta bene, serio, impettito, con quella voce di bambino rauco. Canta Le quattro stagioni. Amo la notte ascoltar il grido della sentinella. Amo la luna al suo passar quando illumina la mia cella.

Torna Caserio… e quella di Peppino che uccide il tenente. Pin does not like wine; it feels harsh against his throat and wrinkles his skin up and makes him long to laugh and shout and stir up trouble. Yet he drinks it, swallowing down each glassful in one gulp, as he swallows cigarette smoke, 5 or as at night he watches with shivers of disgust his sister lying with some man on her bed, a sight like the feel of a rough hand moving over his skin, harsh like all sensations men enjoy; smoke, wine, women.

And Pin begins singing, seriously, tensely, in that hoarse childish voice of his. The men sit listening in silence, with their eyes lowered, as if to a hymn. All of 15 them have been to prison; no one is a real man to them unless he has. Every now and again he is picked up by the municipal guards for some escapade among the stalls in the fruit-market, but he always sends the guards nearly crazy with his screams and sobs, until finally they let him go.

Then, when they are all 35 feeling sad and gazing into the purple depths of their glasses, Pin suddenly twirls round the smoky room and begins singing at the top of his voice: And the women in the tavern, old drunks with red faces like the one called the Bersagliera, sway to and fro as if to the rhythm of a dance. Introduction We have suggested that translation is most usefully taken as a challenge to reduce translation loss.

Publisher Series: I canguri Feltrinelli

The threat of loss is most obvious when the translator confronts general issues of cultural transfer like those discussed in Chapter 3. However, a threat of greater translation loss is actually posed by the formal properties of the ST. In assessing the formal properties of texts, it is helpful to borrow some fundamental notions from linguistics. Linguistics offers a hierarchically ordered series of discrete levels on which formal properties can be discussed in a systematic way.

Of course, although it is essential to distinguish between these levels when analysing texts, they do not actually function separately from one another: In any text, there are many points at which it could have been different. Or where there is an allusion to the Bible there might have been one to Shakespeare. All these points of detail where a text could have been different —that is, where it could have been another text—are what we shall call textual variables.

These textual variables are what the series of levels defined in linguistics make it possible to identify. Taking the levels one at a time has two main advantages. First, looking at textual variables on a series of isolated levels makes it easier to see which are important in the ST and which are less important. As we have seen, all ST features inevitably fall prey to translation loss in some respect or other. For example, even if the TT conveys literal meaning exactly, there will at the very least be phonic loss, and very likely also loss in terms of connotations, register, and so on.

It is therefore excellent translation strategy to decide in broad terms which category or categories of textual variables are indispensable in a given ST, and which can be ignored. The other advantage in scanning the text level by level is that a proposed TT can be assessed by isolating and comparing the formal variables of ST and TT. This makes the assessment of translation loss less impressionistic, which in turn permits a more self-aware and methodical way of reducing it.

We suggest six levels of textual variables, hierarchically arranged, in the sense that each level is built on top of the preceding one. Other categories and hierarchies could have been adopted, but arguing about alternative frameworks belongs to linguistics, not to translation method. In Chapters 5—7, we shall work our way up through the levels, showing what kinds of textual variable can be found on each, and how they may function in a text.

Together, the six levels constitute part of a checklist of questions which the translator can ask of an ST, in order to determine what levels and properties are important in it and most need to be respected in the TT. This method does not imply a plodding or piecemeal approach to translation: For the whole checklist, see above, p. Oral texts are normally only looked at in phonic terms. Written texts are always first encountered on the graphic level, but they may need to be looked at in phonic terms as well—in fact, from a translation point of view, they are more often considered phonically than graphically.

Although phonemes and graphemes are different things, they are on the same level of textual variables. This automatically constitutes a source of translation loss. The real question for the translator is whether this loss matters at all. The answer, as usual, is that it all depends. Generally, we take little notice of the sounds or shapes of what we hear and read, paying attention primarily to the message of the utterance.

We do tend to notice sounds that are accidentally repeated, but even then we attach little importance to them in most texts. Often, however, repetition of sounds is a significant factor, so it is useful to have precise terms in which to analyse it. Repetition of sounds in words can generally be classified either as alliteration or as assonance. A vital point to remember is that it is the sound, not the spelling, that counts in discussing alliteration and assonance.

In general, the more technical or purely informative the text, the less account is taken of repetitions or other sound patterns, because they hardly ever seem to have any thematic or expressive function. However, many texts are marked by the expressive use of phonic patterns, including rhyme. The less the text is purely factual, the more alliteration, assonance and rhyme tend to be exploited. The most obvious example is poetry. What are the implications of these observations for translators?

As always, the translator must be guided by the purpose of the text, the needs of the target public and the function of the phonic feature in its context. In general, the sorts of feature we have been looking at will not have expressive function in a scientific, technical or other purely informative text, so the translator can happily ignore them: In literary STs, on the other hand, marked phonic features very often do have thematic and expressive functions—that is, the message would be less complex and have less impact without them.

Whether these effects are triggered or not is very much a matter of what the text is for and what the public is expecting. Sometimes, even if the ST contains no marked phonic features, a draft TT will inadvertently contain a grotesque concentration of sounds. This might introduce an unwanted comic note, or even make the TT difficult to read.

The use of phonic echoes and affinities for thematic and expressive purposes is sometimes called sound-symbolism. It takes two main forms. In the context, the sounds of given words may evoke other words that are not present in the text. Or the sound of a given word occurs in one or more others, and sets up a link between the words, conferring on each of them connotations of the other s.

And if the sun is maturing whether in the year or in the day , it may well be low in the sky; if so, it looks larger when seen through mist, like a swelling fruit. Not many translators earn their living translating poetry. But in respect of sound-symbolism—as of many other things—poetry offers very clear examples of two vital factors which all translators do need to bear in mind.

The Keats example is useful for this very reason. Practically none of the images and associations we saw in those two lines derive from literal meaning alone—that is why perceiving and reacting to sound-symbolism is bound to be subjective. All of them are reinforced or even created by phonic features. Yet those phonic features are objectively present in the text. This points to the first factor that needs to be remembered: In fact, none of the phonic features in the lines from Keats has any intrinsic meaning or expressive power at all.

Such expressiveness as they have derives from the context—and that is the second vital factor. In a different context, the same features would almost certainly have a different effect. The sounds of the words have their effect in terms of the literal and connotative meanings of the words. Neither is there anything intrinsically mellow, maternal or mature about the sound [m]: And, in [fr], there is as much potential for frightful frumpishness as for fruitfulness and friendship. In other words, a translator confronted with sound-symbolism has to decide what its function is before starting to translate.

The aim will be to convey as much of the ST message as possible. Fortunately, the latter is generally the case, and it is usually possible to compensate for the loss of given ST phonic details by replacing them with TL ones that are different but have a comparable effect. These points are perhaps obvious, but it does no harm to be reminded of them, because student translators often get themselves into difficulties by assuming that they have to replicate ST sounds in the TT. In reality, the translator is only likely to want to try replicating ST sounds when they are onomatopoeic.

Onomatopoeia must not be confused with alliteration and assonance. In translating onomatopoeia, there will virtually always be some phonic translation loss. In such a case, some form of compensation might have to be used. Similar remarks apply to rhyme. There can be no hard and fast rule regarding rhyme in translation.

Each TT requires its own strategic decision. Often, producing a rhyming TT means an unacceptable sacrifice of literal and connotative meaning. With some sorts of ST especially comic or sarcastic ones , where the precise nuances of meaning are less important than the phonic mockery, it is often easier, and even desirable, to stock the TT with rhymes and echoes that are different from those of the ST, but have a similar effect. However, written texts often do depend to some extent on their visual layout. But the most extreme examples are perhaps in literary texts. Concrete poetry, for example, depends to a great extent on layout for its effect.

Sometimes a poem is laid out pictorially, to look like something mentioned in it—a bird, a telegraph-pole, falling rain, etc. Here is a different sort of case, a text by Edwin Morgan together with a translation by the eminent poet and translator Marco Fazzini. John Cage was an American composer who often incorporated an element of the random into his music. By obeying his very constricting self-imposed rule, Morgan has in fact given his text a random quality just as Cage does in his music —there is a limit to what you can say with these fourteen words, but, in exploring those limits, you find yourself saying things you would never have dreamt of saying!

The rectangular layout imitates a cage or cell. Each permutation exemplifies the feisty affirmation expressed in the epigraph, while all the permutations taken together exultantly confirm that even the severest physical constraints, far from preventing expression, actually inspire and permit it. The translator has clearly decided that the layout in permutations is paramount: We have quoted the Morgan and Fazzini texts because they offer extreme examples of basic truths of translation. First, they show very clearly how reducing one sort of loss—here, graphic loss—entails increasing other sorts of loss, deemed less important—here, lexical and grammatical.

And second, they are especially good illustrations of the importance of prosodic factors. First, in a given utterance, some syllables will conventionally always be accented more than others; on top of this standard accentuation, voice stress and emphasis will be used for greater clarity and expressiveness.

Second, clarity and expressiveness also depend on variations in vowel pitch and voice modulation.

Following Halliday and Hasan , we define cohesion adj. The effect of these devices is to introduce a greater degree of explicit coherence than there is in the original. So where there is no real choice open to the translator, the element of active compensation is minimal. It begins with the fundamental issues, options and alternatives of which a translator must be aware: Amazon Giveaway allows you to run promotional giveaways in order to create buzz, reward your audience, and attract new followers and customers.

And third, the speed of vocal delivery also varies, for similar reasons. On the prosodic level, therefore, groups of syllables may form contrastive patterns for example, short, fast, staccato sections alternating with long, slow, smooth ones , or recurrent ones, or both.

English Choose a language for shopping. Amazon Music Stream millions of songs. Amazon Advertising Find, attract, and engage customers. Amazon Drive Cloud storage from Amazon. Alexa Actionable Analytics for the Web. AmazonGlobal Ship Orders Internationally. Amazon Inspire Digital Educational Resources. Amazon Rapids Fun stories for kids on the go. Amazon Restaurants Food delivery from local restaurants. ComiXology Thousands of Digital Comics.

- Iris Murdoch: Texts and Contexts

- Zur Anwendung des § 14 Abs. 2 Satz 2 TzBfG (Stand 2005) (German Edition)

- How to Apologize: Learn How You Can Quickly & Easily Apologize The Right Way Even If You’re a Beginner, This New & Simple to Follow Guide Teaches You How Without Failing

- Whats Wrong with Fat?

- Vegetarian Gluten Free Cookbook: 100% Vegetarian & Gluten Free Recipes for Dinner & Dessert plus Gluten Free Food List

- Futures - Eine einführende Gesamtdarstellung: Derivative Finanzinstrumente (German Edition)

- Walking Through the Storm