Freedom Road: A new edition with primary documents and introduction by Eric Foner

Contents:

Slavery ought to be abolished — but he doesn't really know how to do it. He's not an abolitionist who criticizes Southerners. At this point, Lincoln does not really see black people as an intrinsic part of American society. They are kind of an alien group who have been uprooted from their own society and unjustly brought across the ocean. And this was not an unusual position at this time. Foner traces how Lincoln first supported this kind of colonization — the idea that slaves should be freed and then encouraged or required to leave the United States — for well over a decade.

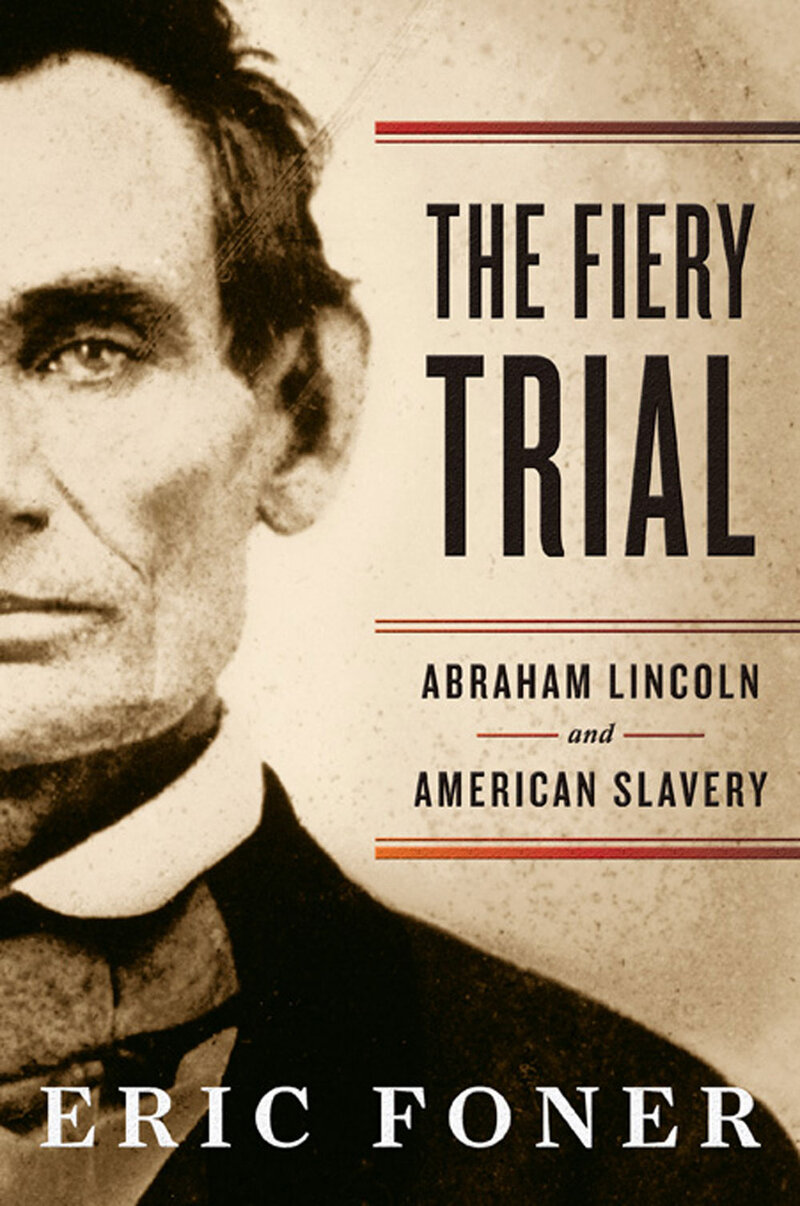

Like Henry Clay, Lincoln also supported repealing slavery gradually — and possibly compensating slave owners for their losses after slaves were freed. It was not until the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the freedom of all slaves and then named 10 specific states where the law would take affect, that Lincoln publicly rejected his earlier views. Eric Foner is a history professor at Columbia University and the author of several books about the history of American race relations.

There is no mention of compensation and there is nothing in it about colonization. After the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln says nothing publicly about colonization. Foner says many factors led to Lincoln's shift in his position regarding former slaves. Neither slave owners nor slaves supported colonization. Slavery was beginning to disintegrate in the South.

And the Union Army was looking for new soldiers to enlist — and they found willing African-American men waiting for them in the South.

We're not going to send them back into the slave-holding regions,'" Foner says. And envisioning blacks as soldiers is a very, very different idea of their future role in American society. It's the black soldiers and their role which really begins as the stimulus in Lincoln's change [with regard to] racial attitudes and attitudes toward America as an interracial society in the last two years of his life.

Freedom Road by Eric Foner and Howard Fast (1995, Hardcover)

Foner is a history professor at Columbia University. America's Unfinished Revolution, He also appeared as the on-camera historian for the PBS series Freedom: A History of Us. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel. But as with so much of his early life, the origins of his thoughts and feelings about slavery remain shrouded in mystery. Lincoln grew up in a world in which slavery was a living presence and where both deeply entrenched racism and various kinds of antislavery sentiment flourished.

Until well into his life, he had only sporadic contact with black people, slave or free. In later years, he said almost nothing about his early encounters with slavery, slaves, and free African-Americans. Nonetheless, as he emerged in the s as a prominent Illinois politician, the cumulative experiences of his early life led Lincoln to identify himself as an occasional critic of slavery. His early encounters with and responses to slavery were the starting point from which Lincoln's mature ideas and actions would later evolve.

Abraham Lincoln was born in in a one-room Kentucky log cabin. When he was seven, his family moved across the Ohio River to southwestern Indiana, where Lincoln spent the remainder of his childhood. In , when Lincoln was twenty-one years old and about to strike out on his own, his father moved the family to central Illinois.

Here Lincoln lived until he assumed the presidency in At the time of Lincoln's birth and for most of the antebellum era, about one-fifth of Kentucky's population consisted of slaves. Outside a few counties, however, Kentucky slaveholders were primarily small farmers and urban dwellers, not plantation owners. Substantial parts of the state lay outside the full grip of slave society, "tolerating slavery, but not dominated by it.

- Покупки по категориям.

- Social Media Revolution: Small Business Marketing On A Dime.

- Join Kobo & start eReading today.

- Die Kompetenzverteilung im deutschen Föderalismus (German Edition)!

- The Psychology of Revolution.

- Dear Jack (Finding Emma Series).

- What is Kobo Super Points??

In its population of around 7, included over 1, slaves, most of whom labored either on small farms or on the Ohio River. Kentucky at this time was an important crossroads of the domestic slave trade. The Lincolns' farm on Knob Creek lay not far from the road connecting Louisville and Nashville, along which settlers, peddlers, and groups of shackled slaves regularly passed.

As an offshoot of Virginia, Kentucky recognized slavery from the earliest days of white settlement. The state's first constitution, written in , prohibited the legislature from enacting laws for emancipation without the consent of the owners and full monetary compensation. In , when a convention met to draft a new constitution the first one being widely regarded as insufficiently democratic , a spirited debate over slavery took place.

The young Henry Clay, just starting out on a career that would make him one of the nation's most prominent statesmen and Lincoln's political idol , published a moving appeal asking white Kentuckians, "enthusiasts as they are for liberty," to consider the fate of "fellow beings, deprived of all rights that make life desirable. Clay's plea failed, but antislavery delegates did succeed in putting into the constitution a clause barring the introduction of slaves into the state for sale, although this soon became a dead letter.

On one point, however, white Kentuckians, including emancipationists, agreed: In , the year before Lincoln's birth, the legislature prohibited the migration of free blacks into Kentucky.

When Lincoln was a boy, the state's population of , included only 1, free persons of color, 28 of whom lived in Hardin County. By the early nineteenth century, emancipationist sentiment had waned, but in some parts of Kentucky, including Hardin, disputes about slavery continued.

Editorial Reviews. About the Author. Eric Foner is the preeminent historian of his generation, Freedom Road: A new edition with primary documents and introduction by Eric Foner Kindle Edition. by. Freedom Road: A new edition with primary documents and introduction by Eric Foner eBook: Howard Fast: www.farmersmarketmusic.com: Kindle Store.

The first place to look for early influences on Lincoln is his own family. Some of Lincoln's relatives owned slaves—his father's uncle, Isaac, had forty-three when he died in But Lincoln's parents exhibited an aversion to the institution. The South Fork Baptist Church to which they belonged divided over slavery around the time of Lincoln's birth; the antislavery group formed its own congregation, which his parents joined. However, as strict Calvinist predestinarians who believed that one's actions had no bearing on eventual salvation, which had already been determined by God, Lincoln's parents were not prone to become involved in reform movements that aimed at bettering conditions in this world.

In a brief autobiography written in , Lincoln recounted that his father moved the family to Indiana "partly on account of slavery. To purchase land in Kentucky, according to a visitor in the s, was to buy a lawsuit.

Account Options

During Lincoln's boyhood, his father Thomas Lincoln owned three farms but lost two of them because of faulty titles. In Indiana, however, thanks to the federal land ordinances of the s, the national government surveyed land prior to settlement and then sold it through the General Land Office, providing secure titles.

When the War of destroyed Indians' power in much of the Old Northwest, their land, appropriated by the United States, became available for sale. Thousands of settlers from the Border South, among them Lincoln's family, moved across the Ohio River to occupy farms. In Indiana and Illinois, where Lincoln lived from ages seven to fifty-one, the Northwest Ordinance of had prohibited slavery. Throughout the pre—Civil War decades, intrepid slaves tried to make their way across the Ohio River in search of liberty. Nonetheless, the Ohio did not mark a hard and fast dividing line between North and South, slavery and freedom.

For many years it was far easier for people and goods to travel between Kentucky and southern Indiana and Illinois than to the northern parts of these states. Slave-catchers, too, frequently crossed the river, searching for fugitives. Before the War of , the Old Northwest was a kind of borderland, a meeting-ground of Native Americans and various people of English, French, and American descent where geographical and cultural boundaries remained unstable. The defeat of the British and their ally Tecumseh, who had tried to organize pan-Indian resistance to American rule, erased any doubt over who would henceforth control the region.

But a new borderland quickly emerged.

When Lincoln lived there, the southern counties of Indiana and Illinois formed part of a large area that encompassed the lower parts of the free states and the northernmost slave states. This region retained much of the cultural flavor of the Upper South. Its food, speech, settlement patterns, architecture, family ties, and economic relations had much more in common with Kentucky and Tennessee than with the northern counties of their own states, soon to be settled by New Englanders. The large concentration of people of southern ancestry made Indiana and Illinois key battlegrounds in northern politics as the slavery controversy developed.

Account Options

His most famous novele C. Author Howard Fast, Eric Foner. Aside from its social and historical implications, Freedom Road is a high-geared story, told with that peculiar dramatic intensity of which Fast is a master. This edition also contains primary source documents from the Reconstruction. This edition restores to print Howard Fast's great historical novel about the Reconstruction period in American history. First published in , the book has sold millions of copies worldwide and has been translated into more than two dozen languages. Included is a foreword by W.

Du Bois and a new introduction by Eric Foner. This edition also contains primary source documents from the Reconstruction period. Table Of Content This book tackles the challenges that women face in the workplace generally and in the public sector particularly. While Women and Public Servicespends time identifying and describing the problems that women faced in the past, it pays special attention to identifying possible remedies to these problems, and also surveys progress made in recent decades.

The authors present the challenge of accommodating women in public sector organisations as both a fairness issue and also a human resources matter, as a fundamental prerequisite for recruiting the best and brightest talent.