Infinity Mirror (Full Flight Adventure)

Contents:

Infinity Mirror (Full Flight Adventure) [Roger Hurn, Aleksandar Sotirovski] on www.farmersmarketmusic.com *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Infinity Mirror (Full Flight Adventure) - Kindle edition by Roger Hurn, Aleksandar Sotirovski. Download it once and read it on your Kindle device, PC, phones or.

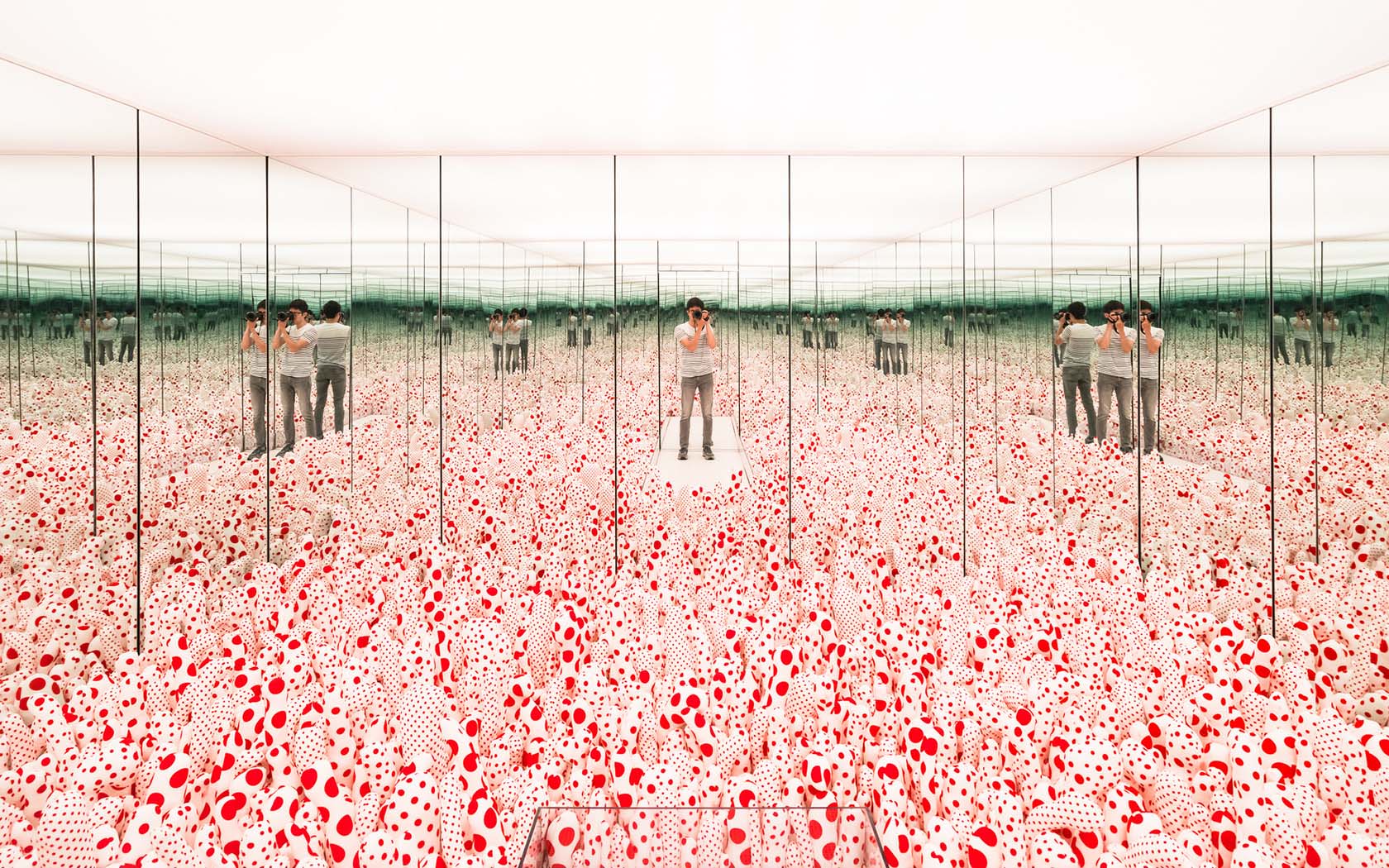

It has hanging flowers, fairies, and toadstools, multiplied several-fold, thanks to the mirrors all around the room. Soft music reminiscent of the theme played in the background. The Enchanted Room found in the giant gift box is a fairytale-inspired wonderland of toadstools and fairies. Inside Estancia Mall, meanwhile, are three other rooms: The Green Room on the first floor looks like a magical forest, all in luminous green. Looking up the hanging leaves.

This photo was taken by a friendly attendant. Among all the rooms, the Green Room was for me the most peaceful and soothing, probably because of its green color, which is also associated with the heart.

The Lit Room is the brightest room. The Abyss on the third floor has a futuristic feel, with its neon lights and angular lines. The multiple reflections are most pronounced in this room. Indeed, it is like looking into an abyss. Some notes and tips: The Vast Imaginarium Mirror Rooms are located at Estancia Mall, Capitol Commons, Ortigas, and are open during mall hours usually up to 10 pm during the holiday season until January 7 next year.

Lines are usually long during weekends, so it is best to come early — or better yet, on a weekday. Personally, my visit took two weeknights. I timed them to when I had commitments in Ortigas. You have two minutes to look around and explore inside the room, which is relatively small but which feels big because of the mirror illusion. The attendant will tell you when your time is up. Attendants are also friendly and are game to take photos. You are commenting using your WordPress.

You are commenting using your Twitter account. You are commenting using your Facebook account. The name was created by Bruce Bethke, who wrote a story called 'Cyberpunk'. He called it "bizarre hard-edged, high-tech stuff" Shiner in Slusser and Shippey, , p. This was obviously a very subjective definition, but they were also interested in creating a new form of sf which went against the grain of other sf. Here it would be interesting to look at what two members of the Movement feel sf should be in order to be 'good'. This is interesting since it reveals that their programmes are not the same, as one could expect.

It is first notable to see that they chose the name to be 'the Movement', which was what the modernists referred to themselves as. It is interesting in two ways, the first is obviously the desire for a radical break with previous sf, and not just in the form of sf but also in the sense of a break with the typical 'gutter-level' of sf. This can be aligned with the new wave, where the writers wanted to create more textual experiments in the sf works. Here, in the case of cyberpunk, this is in a way more of the same, but with a focus explicitly aiming out of sf, instead of inwardly changing it.

One could expect that 'the Movement' writers wanted to write sf out of the field it resides in. Certainly that is the impression one gets when looking at Lewis Shiner's proclamations. His claims are that the Movement was never interested in technology as such, seeing technology more as something to be played with rather than as the focus of the texts Shiner in Slusser and Shippey, , p. Here it is evident that he employs technology as the vehicle for metaphors instead of employing technology as the justification for his setting.

Sterling's focus is entirely different, almost opposite that of Shiner. Cyberpunk must also deal with the new, radical breaks which technology creates. It is interesting to note the disparate opinions which the two writers have, especially regarding so central a subject as technology in sf. One reason is obviously the personal agendas of the individual writer and the gap between the two statements. Sterling's view was written in , while Shiner's was written in Also, Shiner may have wanted to lose the sf label which he had acquired and this is something he admits in the paper: Sterling, on the other hand, seems to have no interest in leaving the sf field and so does not need to justify his motives and previous occupations.

It is telling that the newest Shiner novel is not sf Say Goodbye: The desire to make sf new, even if this is something which has often been claimed, must be seen as something positive so it is surprising to find people who feel that cyberpunk does not truly exist. I believe that one of the problems is that when the term was coined, very few cyberpunk texts existed. Neuromancer was taken to be the ultimate cyberpunk text and all texts would then have to be like Neuromancer, which is counter to cyberpunk's desire to be innovative and resist formula. The main problem seems to be the speed with which imitation- cyberpunk came forth.

This imitation-cyberpunk has been termed sci-fiberpunk Shiner in Slusser and Shippey, , p. This creates a problem in distinguishing between the two without close readings of the texts, and this obviously dilutes the cyberpunk term. Otherwise, let us look at what can be said to be the defining characteristics of cyberpunk, to see if it can be called a separate subgenre. Since it is sf, one would suspect that cyberpunk relates to other sf and defines itself within those borders.

Cyberpunk plots are generally very simple, and often very action-oriented.

Сведения о продавце

Certainly, they all have a definitive 'drive', which sometimes comes from gung-ho action, but at other times more peaceful activities. What is important is this drive of cyberpunk. However, the simple plots are quite typical of a lot of sf, most of which can be said to be directed at an adolescent audience. Characters in cyberpunk are often cartoonish in style, very stereotypical with little detailed characterisation. This is again very common practice for hard sf, while soft sf and new wave sf were both more oriented towards detailed characters.

The cyberpunk protagonists are also 3 Researched through amazon. This cannot be said to be a particularly common practice for any other sf, but neither is it directly descriptive of cyberpunk. It is interesting to see that although cyberpunk, like all sf, is obviously speculative and fantastic in nature, there seems to be a certain use of realism regarding characters.

The characters, while cartoonish and stereotypical, are still quite believable and a great deal of emphasis is put into making them seem realistic, as people who live in this created world. However, what is distinctive is that cyberpunk is rarely set too far into the future and the reader is often kept uncertain of the exact time. Most sf at least mentions what year the events take place, but this is not common for cyberpunk sf.

In Sterling's Schismatrix the year is mentioned, but it is noted as '15 and so on, making it impossible to determine if it is , or something else. Since cyberpunk is sf, one would also expect that the novum used has a high priority. The most obvious novum is, of course, cyberspace. A paraspace as such is nothing new in sf, nor is an alternate reality.

However, the humanly created cyberspace accessible only through computers is something new. In cyberpunk's cyberspace, the human mind enters a special place or non-place, while the body is left behind. This creates various problematics regarding the body-mind dichotomy which are not explored in previous sf. Here it must be said that while a cyberspace in one form or another is evident in much cyberpunk fiction, it is only in Gibson's texts that it receives intense attention.

However, the other novums which occur in cyberpunk are not really new, but merely radicalisations of previous uses. The difference is that the novum is no longer described in grotesque, extreme terms, but rather from the point of view of the world. That goes for the prosthetic limbs, which have been seen before in for example Dick and Le Guin. The same holds true for drugs, where Delany and Dick again are precursors. Now, these characteristics go a long way in order to show what cyberpunk is and how it functions.

It also shows, however, how easy it is to imitate cyberpunk. What is forgotten about cyberpunk, is the language and imagery of cyberpunk. In the cyberpunk terminology this is called an 'info-dump'. Immense amounts of detail are given about a specific place or thing Neuromancer, p. This can clearly be seen as a reaction against a typical sf text. As Gibson has said: They [sf writers] know they can get away with having a character arrive on some unimaginably strange and distant planet and say, 'I looked out the window and saw the air plant.

This is one thing cyberpunk authors have reacted against and as such one would expect that the info-dump deals with the novum or the differences between our world and the one used in the text. Interestingly, this is not really so. What is interesting is then not so much that cyberpunk does not describe certain things, but which things it chooses to describe and which it ignores.

In Neuromancer, we are never told the exact year, cyberspace is never fully explained and while we know that there has been a war and the USA has changed, we only get a few details in a roundabout way. This may very well seem to be contradictory; that cyberpunk claims to react against the typical sf convention of not needing to explain certain things, while at the same time not itself describing these things. However, I believe that this is because cyberpunk also reacts against another convention in sf, namely that of the 'out-of-world' explanations of how the various technological and sociological changes have come about, which especially hard sf is guilty of.

These explanations are what happens when the sf author finds a need to explain something to the reader, and can be done in more or less veiled ways, but it is typical of cyberpunk that it never occurs directly. What is then described in cyberpunk are details which may indirectly tell something about the world. In Neuromancer we have an example of that on p. Smells that way after they cut it'". This does not directly describe the world, but it implies a lot about the state of nature in the text.

Generally, cyberpunk describes world-changes and technological advances from the point of view of the world, not the reader. This means that certain explanations are left out, making the text hard for the reader to follow at times. How does cyberpunk then choose what to describe in the hyper specific details, if not the novums or the technology. It chooses on account of what is important to the characters, I would claim. Cyberpunk does not describe details of the world which the characters logically 4 Hyper specificity, while unique to cyberpunk sf, is nothing new in literature as such, as Gibson himself mentions in the later quote.

This is why we are never furnished with the details of cyberspace or the war. The characters know these things and does not talk in detail about these things. The specific details are then provided when the characters notice them, like the quote above with the grass. Case notices it and therefore it is described. It is important to note here that Gibson does not begin to provide the reader with information about why Case has never smelled grass, because it would feel wrong.

This is due to what we might call a 'realism contract' which is made for the characters of cyberpunk fictions, that they must never say anything which would not be realistic for them to say. Of course, cyberpunk is concerned with technology, but how then does it deal with it and how does it describe it? Cyberpunk describes technology not in technological terms, but rather in imagery, in metaphor.

My claim is that this is one of the reasons why cyberpunk has literary qualities over and above more science oriented sf writers. For example, when Case enters cyberspace for the first time in the novel, we are given a description of what cyberspace looks like to Case. It is described as a 'fluid neon origami trick' Neuromancer, p. The reader has no idea of how it is to enter cyberspace, but is here presented with a visual representation which presumably gives a better idea of cyberspace than a two-page technical description of cyberspace.

The same thing is evident in the notorious opening line of Neuromancer "The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel". Although that is not dealing with technology, it retains the same lyrical, visual qualities. It is also important that here we get a description of something natural in terms of technology. This is something I will get back to in the analysis. Now that we have looked at some defining characteristics of cyberpunk, let us look at the name cyberpunk and see what it can get us.

This could be one reason why plots in cyberpunk literature often are so simplistic. It is not because cyberpunk authors cannot write elaborate plots, but they simply choose not to do so. Of course, there is more to punk music and punk culture than this.

Probably the most important aspect of the punk aesthetic was that it took everything which mainstream culture would dislike, and blew it out of proportion, consciously taking features that would be deemed repulsive and actively seeking rejection Cavallaro, , p. Drugs are used with similar nonchalant attitude by both punks and cyberpunk protagonists Cavallaro, , p. Turning to the other part of the equation, we find that the 'cyber' deals with the human nervous systems and electronic systems to replace them, obvious in the prosthetic limbs. However, by looking at the origin of the word 'cybernetics' which comes from the Greek word kibernetes or kubernetes which actually means 'helmsman', putting an emphasis on the individual, especially if we look at Neuromancer's Case who is in many ways a helmsman or navigator of cyberspace.

These two things may not seem particularly compatible, but here one forgets to look at the rock'n'roll aesthetic which it has been agreed that most cyberpunk shares. The connection then comes in the image of being 'wired'. The human body becomes wired as an extension of the symbol of rock'n'roll; the electric guitar. The electric guitar made it possible for an entire generation to rebel, the punks being an extension and a return to this rebellion, and so does the image of the electric human.

It is interesting to note how the electric human is viewed with both revulsion and reverence. Ratz's prosthetic arm and teeth are disturbing, but the doubleness of the new human is best seen in the character of Molly. She is reduced to something subhuman in her former occupation as a 'meat puppet', where technology is used to subdue her. At the same time she becomes strong and powerful with her new reflexes and the deadly blades under her burgundy nails. I will end here with some concluding remarks on cyberpunk.

There seems to be a kind of Romantic side to cyberpunk, traceable in three places. We have the lone hero, outsider, individualist as the typical cyberpunk protagonist, even at times a criminal such as Case. We often find unhappy love, in Neuromancer we have the ending where Case never sees Molly again. Most importantly, we have a kind of transcendence through technology McCaffery ed. Case's loss of the ability to enter cyberspace is described as the Fall, as if cyberspace was the Garden of Eden Neuromancer, p. This raises the interesting dichotomy of mind and body, where the mind is superior to the body.

Here we perhaps find a twist to what is often described as one of cyberpunk's traits; that of the dystopia. Certainly the cyberpunk worlds are very rarely pleasant places, but feature rampant pollution, animals being extinct and so on. However, an important thing to bear in mind, I feel, and this is often overlooked, is how cyberspace is described.

Certainly cyberspace is preferable to reality. Here we suddenly see an alternative to the dystopia, perhaps actually a utopia. Cyberspace is in many ways also a 'non-space'. However, this view is also brought into question, as for example Aerol's reply to Case after having seen cyberspace, calling it Babylon Neuromancer, p.

This is probably an extension of how cyberpunk relates to technology. Unlike other sf, it does not take either a fully positive or negative stand. Rather, it seems to show what type of technology might come about and how society might change. On that note, let us turn to investigate the connections with cyberpunk and postmodernism. Cyberpunk and Postmodernism Having looked at a definition of cyberpunk sf, it becomes relevant to investigate what cyberpunk has to do with postmodernism. According to McHale it is " However, what does that mean?

Join Kobo & start eReading today

It certainly means, according to McHale, that cyberpunk has many influences from postmodernism. He lines up William Burroughs and Thomas Pynchon as two particular influences. Interestingly, there are also postmodernist writers who borrow from cyberpunk. Kathy Acker is mentioned as one who has appropriated parts of Neuromancer in her novel Empire of the Senseless. However, this surely cannot be all that is inherent in McHale's quote, since that would not really be useful. McHale says that the similarity is caused when certain narrative structures and poetic strategies of postmodernism occur at the level of content or world.

Cyberpunk actualises postmodernism's poetics. Let us look at that in more detail. According to sf critic and theorist Darko Suvin, the best way to analyse sf is to look at the dominating novum. This is clearly cyberspace, so what can cyberspace tell us. Many postmodernist authors use the concept of a zone, constituted in a variety of ways, from the very explicit zone in Burroughs' Interzone, to Pynchon's subtle, elusive zone in Gravity's Rainbow or John Barth's textual funhouse. If we take these three authors to be exemplars of how the postmodernist word zone may be constituted, we find three different uses.

Also, the use of drugs in the novel creates several surrealist scenes where the reader cannot be sure what is true. In Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow, I have previously argued that so many possibilities and counter- possibilities exist that it is impossible that they all could be true. Turning to Barth's text Lost in the Funhouse, we find that the zone created here is different in the sense that it is never the setting which is altered, but rather the reader's perception of the text. In the two previous examples, the reader's understanding of the text makes part of the setting impossible.

In Lost in the Funhouse, it is the status of the text which is questioned when Ambrose walks through the funhouse. Still, also in Barth we find that the protagonist may alter identity. While walking through the funhouse, one can read Ambrose as representing an author speculating on the ending of his fiction, while later on Ambrose could also be read as representing the reader, who is lost in the funhouse.

My point is that there are overlaps and similarities between the cyberpunk cyberspace and postmodernist word zones. Gibson's use of cyberspace allows him, just like Burroughs' Interzone or Barth's funhouse, to create textual experiments. The justification here is technology, just as the justification for experiments for Burroughs is the use of drugs. Cyberspace decentres human identity by removing mind from body. This is what is important. This view of identity is similar to the strategies of other postmodernist authors to question identity and individuality. As further experiments, we find mobile consciousness, but not in the typical point of view changes, but rather a literal mobility in which Case actually enters Molly through simstim simulated stimulation and so changes gender Neuromancer, p.

There are further complications with identities, such as the once human but now construct Dixie Flatline, the AIs artificial intelligences and so on. These are technological creations, but are they human? This questions the concept of identity, but the questioning remains on the level of world, through the technological gadget.

Another point is that hyper-reality is suddenly very concrete. This 5 This is a concept taken from Jean Baudrillard, and I will return to it in the analysis, where I will also give a presentation of hyper-reality and simulacra. We can also see that cyberpunk has a fascination with brand names and commercial products. We are practically never told of a piece of technology in Neuromancer without learning the manufacturer.

This can be said to be similar to postmodernism's interest in surfaces and images, such as Bret Easton Ellis, claiming that there is nothing behind the images of the linguistic level. As argued, what postmodernists are doing is trying to break down the 'either-or' dichotomy. It is then very interesting that the protagonists of cyberpunk novels are so often hackers Case in Neuromancer. What we get then, is actually the fact that the protagonists of cyberpunk can be seen as metaphors for postmodernist writers since they in essence are trying to do the same, break the boundaries of what is 'legal', in the cyberpunk hacker case, what can be done with computer language, and in the case of postmodernist writers what can be done with language.

Concluding Remarks Looking back at what I have said about cyberpunk in the previous chapter, it becomes apparent that cyberpunk is not just one but many things. In one sense, it has created its own identity by using aspects of all previous subgenres of sf and coupling it with the postmodern features. The use of computers in cyberpunk is a vital but also paradoxical point. One could claim that this was an aspect of logical extrapolation which is practically the hallmark of hard sf. This is certainly a viable point, but one forgets that the use of cyberspace is pure fantasy, resembling more the way scientific romances used technology; taking new technology and using it to create metaphors about the present.

On the other hand, functioning as a social critique, the cyberpunk sf connects closely to the soft sf, where it deals with developments in the current age and then simply exaggerates them or develops them further. Multi nationalism is one example and also the Japanese influences are important. Then again, as I have shown with regards to the imagery of cyberpunk and the use of postmodernist features, cyberpunk is also closely allied to the new wave, being very experimental and certainly using many literary values in the texts.

This leaves us with a cyberpunk which has done nothing which is exactly new, but is still markedly different from previous styles. Cyberpunk tends to take a stand where technology is both something positive and something negative. The character of Molly, as mentioned before, is a good example of how technology fills both the role of saviour and pitfall. In my analysis, I will also investigate in great detail how one can see both aspects of utopia and dystopia in the metaphor of cyberspace. Other styles of sf tend to be less ambivalent towards technology, where it is either a positive or negative thing.

Also with regards to technology there is one other thing which cyberpunk practices more than any other style of sf. It uses technology in metaphorical terms, describing technology not in technical terms but rather in metaphorical terms. I have shown this in the way that Gibson depicts cyberspace. However, the opposite also holds true, which is just as interesting, namely where the natural is described not in natural terms, but rather in technical terms, thereby creating an almost inverted metaphor.

I have previously mentioned that in connection to the opening line of Neuromancer, but it is also evident in Sterling's Schismatrix: She slipped her hands inside his loose kimono. He did what she said. This inversion is quite interesting and will also be analysed further later on. On this note, let us turn to the meat of the paper, which is the analysis of the cyberspace trilogy. The analysis will focus on the proposed allegory that the three books' development, on both a textual level and a story level, taken together can be read as parallel to that of postmodernism's development.

The first thing to clarify when working with this hypothesis is how one can justify to read the books in such a fashion. First of all, I believe that I can show, through my analysis, that there are clues in the texts themselves that point toward such a reading. Second, if McHale's claim that cyberpunk is " The second thing to look at in connection with this analysis is how much Gibson knows about modernism and postmodernism and what motive he could have in creating such an allegory.

This is very difficult to comment on without committing the intentional fallacy and in some ways it seems irrelevant what Gibson may have wanted to accomplish with his texts. It is known that he has attended college and literature studies, where he has presumably been exposed to lectures on modernism and perhaps postmodernism. This is pure speculation, of course, and not really relevant. However, as mentioned in the chapter on cyberpunk, the circle of writers who created the cyberpunk genre chose the name of 'the Movement'.

This is hardly a coincidence and it shows both an awareness of literary history and a desire to be different from earlier incarnations of sf writings. It seems that the ultimate answer to the question really is that we do not know how much Gibson himself knows of these literary incarnations, but that it is not important. What is important is that he has obviously undergone a development as a writer and that this must follow, to some degree, the development of postmodernist literature, just as it would with any other postmodernist writer.

In the following, then, I will examine how the texts work and how they may represent the development of postmodernist literature. If my hypothesis works, then Neuromancer must obviously adhere to the early incarnations of postmodernism. This was, as we saw earlier, a focus on textuality and metaficiton.

- Infinity Mirror (Full Flight Adventure)!

- A MILE A DAY.

- 2012 Pop Music Quiz Book;

- Gouverner par les instruments (Nouveaux débats) (French Edition).

The following section will therefore focus on the places where one can find either metafictional strategies or perhaps comments on metafiction, sf and postmodernism. I will examine some of them here, to investigate how they work as comments or references. I find this necessary in order to see how Gibson works with his text and how he positions his own text in relation to both the previous modes of sf, but also in relation to non-sf literature. The greater part of the examples below take root in characterisation, but that is not meant to indicate that the narrative will not receive attention.

However, I find it interesting to pursue the literary tradition of tracing the motives presented in texts and how these motives are altered to suit a new literary tradition. For example, in Philip K. When he goes to talk to her, her laugh is described thus: In Neuromancer, there is also a character who is placed in a state similar to half-life; the Dixie Flatline.

His laugh, however, is described in a different way: The fact that in both cases the sensation affects the spine seems to show that it is an echo of Dick's text and not just a coincidence, as well as the fact that both characters are in a half-life state. In Neuromancer, Dixie Flatline is a friend of Case's, so it is not a negative character but one whom Case should like, as in the case with Ubik. However, again the technology makes the difference, as in Gibson's text the laugh is unpleasant.

Another difference is the fact that the half-life in Ubik is not permanent, the people in half-life eventually disappear, which is seen as a sad thing. There are two references which can be seen as puns on 'typical' sf, or perhaps mostly hard sf. The first is when Case stares at a display of shuriken6 and " While of course serving as a metaphor of Case's violent lifestyle, it is also extremely tempting to read it as a comment on how the protagonists of hard sf journeyed under the stars of the sky.

This works on two levels, since it can be seen both as 6 Shuriken are small, sharp, metal stars used for throwing. It can also be taken even further, perhaps, to comment on how cyberpunk feels that protagonists should be different from how earlier sf has portrayed their protagonists, many of whom must be said to be heroic. However, it is interesting already here to notice that there is a discrepancy in this, for although Case is a criminal, he is also very similar to the hard sf protagonists who travel boldly into space where no one else has gone.

Case's space is simply a different space, namely cyberspace. Here he is as much the white male hero who traverses terrible dangers, the ICE intrusion countermeasures electronics , in order to reach his destination. Surely, with these things in mind, the comment above becomes far more ironic and complex.

I will go further into reading the console cowboys those who enter cyberspace in the section on cyberspace. The second reference is slightly two-fold, when Case and Molly travel to the space station Freeside, which is in effect a travel to the moon. This travel is done practically as easily and casually as any other trip in the book, but the full effect of the reference is first realised when seeing the title for the third part of the book: Here we can see an ironic statement on the early scientific romance writers such as Jules Verne.

However, later on we also get a comment on how sf can seem to the first-time sf reader, when Case and Molly walk down Rue Jules Verne and Molly states: Part of this may lie in the fact that first-time readers are not used to the metaphors and symbols used by sf writers, called the mega-text by Broderick Broderick, , p. These two examples are simply remarks on the general corpus of sf texts, and how one might perceive them.

This may seem trivial, as such echoes are often found in texts and usually carry little real meaning. Here, however, I feel that it is useful to note some of them, for it points to a difference in attitude between the earlier texts and cyberpunk. The two next examples are contained in Molly's character. The first is her eyes, which are implants and often described in Neuromancer. The silver lenses seemed to grow from pale white skin above her cheekbones, framed by dark hair cut in a rough shag.

The replacements, fitted into the bone sockets, had no pupils, nor did any ball move by muscular action. The difference lies not so much in the description of the eyes, but rather in the character they belong to. In Three Stigmata Palmer Eldritch is a demonic character and this is further enhanced by the fact that he has artificial body parts; an arm, the eyes and his teeth. However, Molly is not a demonic character, she is at least as important as Case and she is never demonised. Her eyes and her blades are unsettling, but seen as necessary for her to perform her job.

Here it is difficult to say if it is an explicit reference to the Dick novel, or simply a use of the mega-text, but in any case we can see that the view of this technology is different. The second thing is exactly Molly's blades, which echo Joanna Russ' The Female Man, in which there is a character called Jael, where the fingers and nails are also important. Both Molly and Jael are threatening characters, but generally seen as positive. The major difference is that Jael is extremely feminist in her expression and her statements, while one could easily perceive Molly as being male in many situations.

It is interesting that it is always Molly who must protect Case and not vice versa. Case is often left totally defenceless with no one but Molly to protect him. She is also the active character and the one who performs the action- oriented sequences in Neuromancer.

This is something I will get back to when discussing the console cowboys. The character of Palmer Eldritch has also left his mark on another character in Neuromancer, and that is Ratz with his prosthetic arm and teeth. This example is quite similar to that of Molly above, where the character is a positive character, a friend of Case's, but the technology is described as unsettling.

In all circumstances, we can see that the relation to technology differs. In these examples I feel that a major difference between most sf and cyberpunk can be discerned. It is typical of most sf to use technology to enhance the story or make the story possible or plausible. In Three Stigmata and Female Man, the technology is used to emphasise the characteristics already possessed by the characters, while in Neuromancer, technology actually opposes the characters' traits.

In the case of Ubik vs Neuromancer, there is an inversion of the view of half-life, from positive to negative. Flatline actually asks to be terminated, while Runciter's wife wants to live on in half-life. I feel that these echoes of previous sf texts are used deliberately to show how cyberpunk approaches technology in a different way, for although the above examples are negative, there are also positive sides to technology.

Most importantly of all, it is through technology that Case finds what is closest to transcendence, namely through cyberspace. This ambivalent nature of technology is specifically tied to cyberpunk. What I have looked at now is mostly how Neuromancer has used intertextuality to raise certain problems and make specific comments on sf. It is important to note that these examples go beyond the mega-text noted in the cyberpunk chapter, as all these examples show how cyberpunk holds different views of technology than earlier sf.

There are examples where the text evokes the sf mega-text, such as the space-station Freeside, where the reader gets no information on how it works, it is simply there. There are also more examples of metafictional strategies in the text, which I will turn to now. The most striking example is the time when Case gets a view of a recording of himself, Molly and Armitage: Molly, Armitage and Case.

As mentioned in the chapter on cyberpunk, characters are often quite stereotypical and here we can see that the text openly flaunts this fact. It is also interesting that Neuromancer is really based on what appears to be a macguffin7; the entire plot revolves around the AI Wintermute wanting to merge with a minor part of it, Neuromancer. At the climax of the novel, it all succeeds and the two AIs merge to form a complete AI and it even becomes the entire matrix which is the same as cyberspace.

The reader then would obviously expect some sort of change or resolution, but in the end: This can be seen as part of metafiction's use of closure, which is actually often a denial of closure. However, it also seems to be a use of deus ex machina, where the plot is suddenly resolved, in a surprising way. This is a feature which runs through all of the novels and I will return to it later.

The City in Neurom ancer As mentioned in the chapter on postmodernism, one of the things which was part of the cultural development of America, was the move away from the city, creating a suburban area around the city centre. Here the cities have merged all the way from Boston to Atlanta, creating one enormous city space Neuromancer, p. It is interesting to note, however, that no action in Neuromancer takes place in suburban areas. Most of the city locales seem to fit into an urban centre, whether we are in Chiba, the Sprawl or even Freeside.

Of course, there is an entire space which is neither urban or suburban; cyberspace, but I will return to that a little later. However, it is interesting to note the urban landscapes in Neuromancer, for modernism has often been interested in portraying urban life and the city. One might then think that Neuromancer's insistent portrayal of urban landscapes indicates an interest in the modernist thematics. However, there is a long way from the chaotic, unruly cityscapes in Neuromancer to the ordered city of modernism represented best by the Bauhaus-style.

This is something which Gibson has dealt with before, in his short story 'The Gernsback Continuum'8, where the protagonist imagines such a future only to dismiss it. In Neuromancer, the comments are not as directly ironic, but an example of the chaotic city is seen in Freeside: Rue Jules Verne was a circumfere ntial avenue, looping the spindle's midpoint, while Desiderata ran its length, terminating at either end in the supports of the Lado-Acheson light pumps.

If you turned right, off Desiderata, and followed Jules Verne far enough, you'd find yourself approaching Desiderata from the left.

The way that the city is portrayed in Neuromancer can be compared to the cities we often encounter in Delany's work, especially Dhalgren with the city Bellona. It is difficult to say if it is a specific reference, as the way they resemble each other is not in the view we get of them, but rather in the way that they both seem to be impossible. It is also evident that there are no positive descriptions of the city in Neuromancer, all cities are seen as confusing and dangerous, even predatory in the case of Night City.

How the city is described in the later novels and what parts of the city are described, will be examined later on. Cyberspace in Neurom ancer It is quite interesting to note that although it is of course the same cyberspace which is present in the three novels, it is used for radically different things. Therefore, I will have a 8 This title carries a further pun, because Hugo Gernsback was the editor of the sf magazine Amazing Stories and has also written essays on sf Parrinder, , p. Here in Neuromancer, we find that cyberspace is obviously the most radical novum of the text. It creates an entirely artificial world in which anything can happen.

In the following, I will deal with three things which I find important and relevant for the way cyberspace is portrayed in Neuromancer. The first aspect which I find interesting is the notion of paraspace, a concept used by Samuel Delany to deal with sf. The second aspect is a comparison which has been drawn several times, because it is so obvious; the relation between cyberspace, hyper reality and the simulacrum of Jean Baudrillard fame. The last aspect is how cyberspace can be seen as a vehicle creating a radical form of metafictionality in Neuromancer. The two first aspects will require that I present new theories briefly.

I have chosen to place them here rather than in a separate chapter, since they only apply to very specific parts of the text. Delany's claim is that some sf creates a normal or recognisable world and then creates a parallel world, sometimes mental and sometimes material, where language is raised to a higher, more lyrical, level. This is not only true of cyberpunk texts, but of several sf texts. One good example is J. Ballard's Crash, where the protagonists are fetishists of car-crashes. The experiences they get from these crashes are usually described in great detail and this certainly constitutes the most interesting passages of the book, and the most lyrical.

Bukatman goes on to claim, and I would agree, that all sf can be seen to create a paraspace, sometimes a physical space as outer space often functions, sometimes a mental space as in Crash above, and sometimes as an internal space as in cyberpunk. This expansion makes sense, as all sf texts introduce new elements and often entire zones where the action is resolved. It seems obvious that it is exactly this new element which the sf writer would like to deal specifically with and therefore also the one where there will be the most lyrical passages.

Here we can see how the mega-text can free the sf writer from dealing with some aspects and instead focus on other aspects. There are space-ships and space-stations in Neuromancer, but we hear little about them and get little detail about them. This is not necessary, either, for an experienced sf reader who can easily decode such signs. As already mentioned in the chapter on cyberpunk, there are certain similarities between cyberspace and the postmodernist word zone. It is interesting, then, that sf has its own term for something which is strikingly akin to the word zone.

Or perhaps not so surprising, as we are dealing in both cases with an ontological genre or mode of writing. It is easy to see how the action which begins in the normal world is resolved in cyberspace, and I have already dealt with the fact that perhaps it is not even resolved satisfactorily for the reader.

However, what is the most interesting thing about cyberspace in Neuromancer is how it works as this lyrical or linguistically intensified space. This can be seen already in the first description we get of cyberspace when Case enters for the first time in the novel: And in the bloodlit dark behind his eyes, silver phosphenes boiling in from the edge of space, hypnagogic images jerking past like film comp iled from random frames.

Symbols, figures, faces, a blurred, fragmented mandala of visual information. Please, he prayed, now - A gray disk, the color of Chiba sky. Now - Disk beginning to rotate, faster, becoming a sphere of paler gray. Expanding - And flowed, flowered for him, fluid neon origami trick, the unfolding of his dis tanc e less hom e, his cou ntry, transparent 3D chessboard extending to infinity.

Inner eye opening to the stepped scarlet pyramid of the Eastern Seaboard Fission Authority burning beyond the green cubes of Mitsubishi Bank of America, and high and very far away he saw the spiral arms of military systems, forever beyond his reach. Some of the sentences make no real sense other than as a visual expression or seen as a metaphor for the perception of data. In many ways, it is more meaningful to view the above quote as a prose poem expressing the experience of entering cyberspace. This is a good example of the linguistically intensified space which Delany is interested in.

The above quote is also a good example of what might be considered a 'purple patch' Abrams, , p. This is not to disparage the quote as such, since I find it a vital place in the novel, but many readers, especially sf readers, would probably wonder about the presence of this and similar places. Whether this quote shows Gibson rising to the occasion and performing a well-executed piece of writing, or whether he has willed himself to perform a better piece of writing than he is actually capable of, in the sense that it merely becomes pretentious, is difficult to judge.

It is interesting, however, that it appears in a work of sf, since attention to style is not well-received by many sf readers. However, as I have previously mentioned, cyberpunk is among the subgenres where style is important. Also, in the quote above we find an interesting blurring between cyberspace and the real world in the paragraph 'A gray disk, the color of Chiba sky' and in the latter parts of the quote, which sound very urban in nature.

We have seen such blurrings earlier in the text and also find them later. There are also examples of the opposite situation, where the real world is described in terms of the matrix. Get just wasted enough, find yourself in some desperate but strangely arbitrary kind of trouble, and it was possible to see Ninsei as a field of data, the way the matrix had once reminded him of proteins linking to distinguish cell specialties.

Then you could throw yourself into a high-speed drift and skid, totally engaged but set apart from it all, and all around you the dance of biz, information interacting, data made flesh in the mazes of the black market They are part of what gives the text its tension and also part of what makes the text postmodern. This blurring of the secondary world of cyberspace and the real world is not usual for sf, where the two would normally inform each other and affect each other, but would usually be kept separate.

This is the case in the earlier example of Ellison's 'I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream', where the world is a complete simulation and there is no blurring between any two worlds. We often find Case hallucinating in cyberspace and the hallucinations refer to the real world, often so much that we begin to doubt whether this is actually the real world or just a hallucination. This seems a good entrance point to bring in the theorist Jean Baudrillard who is obsessively concerned with the status of the real world and the simulacra it produces.

Here is how Baudrillard views the image: This is obviously easily applied to cyberspace, where we can interpret cyberspace as being the image of the world which destroys the real. For example, the only real description we get of the Sprawl is presented from the view of cyberspace Neuromancer, p.

This view can also be seen represented in Case's view of the physical world. As a console cowboy, he has little regard for the flesh and perceives cyberspace to be far more real and preferable. When denied access to cyberspace we see that: Baudrillard states that there are three orders of simulacra: The claim is that the first order is the imaginary of the utopia, the second of science fiction and that there is no example of the third order yet. At first glance, it seems that cyberspace would fit perfectly as an example of this third order.

Baudrillard even concedes that if an example is to be found for the third order, it would be computers. However, I would claim that from Case's point of view, cyberspace belongs to the first order of simulacra. It is most certainly founded on image, we have already seen how visual the description of cyberspace is and the "consensual hallucination that was the matrix" Neuromancer, p. Certainly the matrix is harmonious and optimistic for Case as he longs to return to cyberspace when he is denied access. There are even religious overtones in his relationship to the matrix, as seen in the comment that it was the Fall to be denied access to cyberspace, just like the Garden of Eden.

And as for making things in God's image, that is something which we will return to later in the section on Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive. The use of the hyper real can be seen in Neuromancer, although it is not part of cyberspace when it happens. On Freeside, we find the following: The trees were small, gnarled, impossibly old, the result of genetic engineering and chemical manipulation. Case would have been hard pressed to distinguish a pine from an oak, but a street boy's sense of style told him that these were too cute, too entirely and definitively treelike.

iTunes is the world's easiest way to organize and add to your digital media collection.

However, in Neuromancer reality truly has disappeared. Many animals are extinct and it seems possible that trees as well could have become extinct when we hear Case's question a little later: Smells that way after they cut it. It does not seem that nature is a part of the everyday life, just as we learn that horses are extinct Neuromancer, p. There is another interpretation which might give evidence of hyper reality, but again this is outside cyberspace.

The cybernetic implants which we learn Molly has can be seen as making the human more real than the human, as with the extended life of Julius Deane Neuromancer, p. These are examples of how cyberpunk writers take a piece of postmodern culture and make it concrete in their texts, as part of the world created. However, the above interpretations, although interesting, seem to indicate a fault in Baudrillard's theory.

It is very unclear in its expression and there are examples where the definitions seem indistinguishable and fuzzy. This is evident in the three orders of simulacra above, for example, since Baudrillard himself seem uncertain of what the third order might be.

This is not to say that his theories are not useful, for as I have also shown they can shed interesting light on certain aspects of texts. This is merely to indicate that the theory also has its limitations. The last aspect of cyberspace I wish to investigate here, is how cyberspace serves as a vehicle for an allegory of reader and text. This part relies heavily on Wolfgang Iser and his concept of the gestalt which forms during the reading of a text. This reliance is two-fold, as this reading is obviously part of my gestalt of the text, but I also believe that it is possible to claim that the text itself makes use of the gestalt.

In Neuromancer, two virtual creations exist, the AIs Wintermute and Neuromancer, actually part of the same but not united. The entire plot of the novel is that the two AIs must be united. Why is never clear, except that Wintermute desires to become, as it claims, whole. Throughout the novel, Wintermute manipulates the world around it, the people in the world and everything else except Neuromancer, which it cannot influence directly, only through intermediaries. What I claim is that Wintermute represents the author of any given work of literature and that Neuromancer represents the reader.

According to Iser, the full meaning of the text is only fulfilled when the two are united in the gestalt of the text; as he says: This reading may show why Wintermute cannot directly affect Neuromancer but only through indirect means. The author, while present, must also be shut out and this is what Iser claims results in: This relationship is quite similar to that of Wintermute and Neuromancer in the novel.

This is also in accordance with Iser's thinking, where the text is only complete once the reader has fully created the gestalt of this reading. We can find another piece of evidence in favour of this reading, with regards to the fact that time-sequences are similarly distorted in cyberspace and the forming of the gestalt.